Arguments (in 140 Characters or Less)

A week or so ago, education historian Diane Ravitch and Department of Education spokesperson Justin Hamilton got into a bit of a sparring match on Twitter over the role of entrepreneurship in education.

Their argument followed a tweet from Ravitch in which she posited two opposing forces struggling to shape the future of education: entrepreneurs versus educators. “Which side are you on?” her tweet implied.

Who will transform education: entrepreneurs or educators?goo.gl/srER4

— Diane Ravitch (@DianeRavitch) May 19, 2012

Hamilton responded “both” and suggested that to frame it this way – entrepreneurs versus educators – is a “false choice.” Ravitch in turn blasted the DOE for promoting educational for-profits at the expense of educational equality. When Hamilton said he thought Ravitch’s work as a passionate writer and speaker was itself entrepreneurial, she said she was insulted to be compared with the likes of the for-profit cyberschool corporation K12.

Ed Week’s Jason Tomassini did a great job of storifying their back-and-forth, capturing the tweets and providing some of the backstory to their disagreements. It was a disagreement played out on Twitter, of course, and perhaps we should just let it slide that in 140 character-snippets, we tend to type crude proclamations rather than nuanced explanations.

Education Shorthand and Dichotomies

But we avoid the nuance too often, I think.

Much like the term “ed-tech” is simply shorthand for a broad set of topics around “education” and “technology” – teaching, learning, budgets, policies, hardware, software, privacy, community, and so on – “entrepreneur” seems to have similarly muddied meaning (albeit a meaning that becomes somewhat clearer when placed in opposition to “educator.”)

This opposition is related to other dichotomies often invoked in education debates:

- For-profit versus not-for-profit

- Exploitation versus collaboration

- Private versus public

- Proprietary versus open

- Elite versus equitable

- Risk versus security

- Free market versus government

- Individualism versus community

- Institutions versus individuals

- Corporations versus individuals

- Corporations versus startups

- Selling versus sharing

- Industry versus teachers

- Innovation versus inertia

- Bosses versus unions

- Money versus mind

- Extrinsic versus intrisic

- Bigger bottom line versus greater good

- Bad guys versus good guys

- Outsiders versus insiders

I don’t mean to imply here that these oppositions all map neatly on top of one another – that all things teacher-ly live in that right-hand column while all things entrepreneur-ish stand in the left, and from there emanates all things good or bad, stagnant or transformative. Nor do I mean that these nouns and adjectives and verbs (and professions and people and institutions and values) are always and necessarily in opposition.

Clearly it’s much messier and more complex. Although sloppier, the shorthand, the caricatures, and the dichotomies are easier to invoke -- particularly online.

The Entrepreneurial Polis

There have been two stories in the news this past week about entrepreneurs that I think are worth highlighting here – examples of just this sort of complexity when it comes to private and/or public endeavors and our expectations surrounding risk-taking and the greater good.

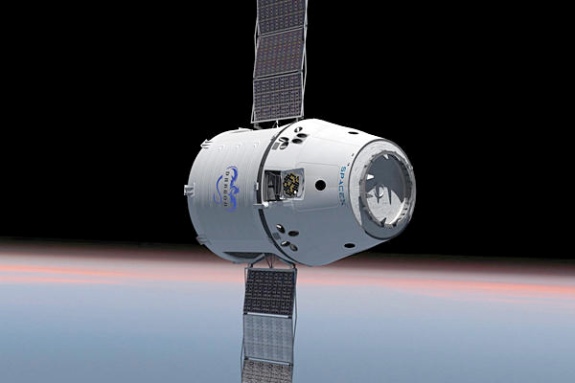

The first is the story of Elon Musk, co-founder of the online peer-to-peer payment site Paypal, the electric car company Tesla, and the space transport company SpaceX.

Last week, SpaceX became the first private company to carry a cargo load, via its Dragon spaceship, to the International Space Station.

While, sure, space travel is of a different magnitude than education, I do think of it as a public good – not even a national public good, but as the International Space Station suggests, a global one – one that matters for all of humanity. (These are my Star Trek roots showing, I do realize.)

But NASA’s budgets (that is, "your tax dollars at work") have been trimmed in recent years – manned lunar missions, let alone trips to Mars, have ended; the Space Shuttle program shuttered. If the government does not maintain funding levels, if it cannot foster (fund) innovation, then what? If we as a nation (or at least, our elected representatives and their control over federal funding) cannot dream big and build big, who will?

Make what you will of comparisons between SpaceX, NASA, and public funding for "innovation in education."

But I wish the world had more Elon Musks, certainly not fewer. I wish the tech and the education and the public sector had more Elon Musks. I wish too that the big dreamers and visionary builders like him would focus on education – and in the ways that are as truly disruptive as Tesla, SpaceX, and PayPal have been. I’m not talking more educational iPad apps here. I’m not talking about the LMS v2.0. I’m not talking taking offline systems and simply digitizing them and calling that “innovation.”

I am talking about big, big thinking and big, big risk-taking -- what Paypal did to the banking and credit card industry, what Tesla could do to gas-guzzlers, and what SpaceX could do for human space flight.

See, I’m talking entrepreneurship.

The second story from the past week or so is a very minor footnote in comparison. It doesn’t involved space travel, manned or un-manned. It involves ClassConnect founder Eric Simons, featured in a CNET story about his squatting at AOL HQ. See, Eric didn’t have the money to pay rent in the Bay Area. He opted to scheme more to protect the future of his startup – Entrepreneurship 101 – over a comfortable place to stay. He figured out that his key-card gave him all-hours access to his offices; and he decided that he'd just stay there rather than find another place to live.

What’s been interesting – and I should note here, that I’ve known Eric for a while now and have written about his startup twice (here and here) – is that none of this recent press about his couch-surfing has brought up the fact that he’s building an education startup, one that is free “for now and always” for teachers. None of them really talk about race or gender and who can get away with camping out in the offices of AOL either. Eric was 19 at the time he spent couchsurfing at ImagineK12 (he’s 20 now); but he's always spoken clearly and passionately about the teacher who intervened in his disinterestedness in high school, and who helped put him on the path to build technology solutions to help solve that.

Squatting at AOL is, of course, a different sort of risk than sending a rocket to the International Space Station. It’s a different scale. It’s a different vision. But it’s a risk nonetheless. It’s a risk that entrepreneurs are expected to take. And it’s something that I admire, even when the space (not the intergalactic kind) in which they’re innovating is one that we think of as “public,” even if they make money doing so. I’m interested in the mission, even if I don't care much about the money.

The Blogger’s Apologia

Following Ravitch and Hamilton’s Twitter spat, New Schools Venture Fund penned a response praising education entrepreneurs and contending that the villainy assigned to them by Ravitch was a complete mischaracterization. Entrepreneurs with “big eyes for profit and little respect for teachers,” writes NSVF partner Jonathan Schorr – “These are not the education entrepreneurs I know.”

Of course not. And New Schools Venture Fund is hardly an impartial observer here. It’s an investment firm – albeit a non-profit “philanthropic” one – that funds these very entrepreneurs. As such, it’s hardly going to say that it’s investing in a bevy of Snidely Whiplashes, scheming to tie public school educators to the train tracks to be crushed by the engines of Progress and the Free Market. These entrepreneurs are “heroes outside the classroom.” (Schorr’s words). Dudley Do-rights all ’round (mine).

More cartoons and caricatures, I realize, but deliberately so.

Like the folks at NSVF, I know a lot of education (startup) entrepreneurs (although I know them through my work as a journalist and not as an investor – both roles color relationships, no doubt). They’re neither Snidelys nor Dudleys (they are mostly men though.) They’re neither villains nor saviors. Their intentions are good – “improving education” sounds meaningful in theory, if not always following through in practice – and even if sometimes they have little depth of knowledge or theoretical sense about what “improving education” means, they’re willing to listen – to me and (more importantly) to teachers.

NSVF insists that “for the folks we talk to every day, mission is the most important thing, and few expect to end up rich.” Perhaps they do; perhaps they don’t. Will some of them some day become multimillionaires? Yes. Will some of them join or lead corporations? Yes. Will some of their startups be acquired by Pearson (and break my heart)? Probably. Is there investor pressure to think about the education system in certain ways (and build accordingly)? Yes. Of course. Can we customers and educators and supporters and critics offer pressure too? Yes, at this moment in time more than ever before. We should seize that moment.

And yet, when Schorr says that Ravitch’s “comments seek to drive a wedge between teachers and those who work to improve public education through entrepreneurship and advocacy,” it’s clear the call for a more nuanced approach to thinking about education entrepreneurship still involves opposition and divisiveness. Again, “Which side are you on?”

Entrepreneurial Ambivalence

Me, I’m ambivalent. Passionately so.

I’m not sure I’d ever use the word “entrepreneur” to describe what I do. I’m a writer, I tell people. I did quit my day job several years ago in order to work for myself, and I’ve since incorporated a business. By some definitions, I guess, that makes me an entrepreneur.

Perhaps.

If you define “entrepreneur” as someone focused on profits, then I’m definitely not one. I don’t make much money doing what I do, let alone turn a profit, let alone fixate on doing so. The money doesn't drive me to write. Rather, I’m driven by a mission: to document and analyze education technology developments – the industry, the technologies, the implementations, the learning processes and outcomes – and to move the conversation forward in a way that supports individual learner agency and the greater public good.

It’s important to note here that when I quit my job back in 2010, I worked for an ed-tech non-profit, one with (ostensibly) a similar mission to promote “excellence in education” through the advancements in technology. But I left in part because didn’t feel like I was making much of a difference. Before that, I left higher ed (I was working on a PhD) because I felt that the institution just wasn’t well-suited to what I needed to do in order to make a difference, in order to support my family, in order to have autonomy and integrity and voice.

I had to go out on my own. I had to be unfettered by bureaucracy and hierarchy and institutional inertia. I had to be nimble and hard-working and brave. I had to be loud. I had to take risks.

I had to be entrepreneurial.

The problem with risk-taking around education entrepreneurship, of course, isn’t just one of money, although that’s probably what most investors (and many public officials who make schools’ budgets) care about. When we talk about risk-taking and education, we are talking about children. We're talking about human lives. And when we talk about risk-taking and a public education, we’re talking about all of us – about the public good.

But take risks we must. Otherwise -- with a nod here to Elon Musk -- we're stuck in the same orbit that's kept us close for millenia. And we shouldn't be satisfied with the status quo. Nor should we accept the arguments made by those in power -- in power in both the private and public sector -- that our complacency is right or good or better than the alternatives. Of course, nor should we assume that innovation and risk-taking are necessarily an improvement or necessarily transformative.

Entrepreneurship and education are far more complex than that -- in no small part because we aren't just talking about systems and control. We're talking about people.

Photo credits: SpaceX, Rankynphile.com