Election Night Racism on Twitter

Like many people, I spent Election Night tuned in to Twitter, watching the results via my social media stream rather than via television. It felt more participatory than passive. It felt more immediate, less contrived.

Like many people, I spent Election Night tuned in to Twitter, watching the results via my social media stream rather than via television. It felt more participatory than passive. It felt more immediate, less contrived.

As a reflection of society, the responses on Twitter were varied and, not surprisingly, politically divided. And as a reflection of society too, it wasn't surprising (sadly) that there was a significant uptick in hate speech on Twitter as people reacted to President Obama’s re-election.

Locating the Racists

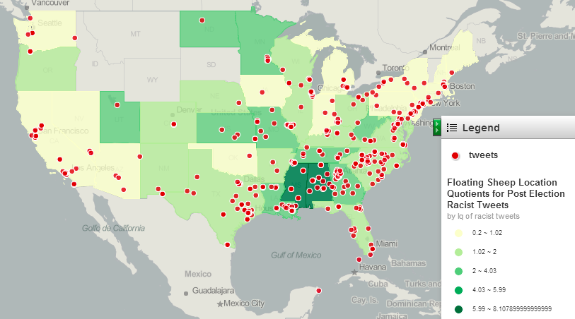

The “geography of information” website FloatingSheep.org aggregated some 400 racist tweets from Tuesday night, mapped them, and compared states’ racist tweeting patterns. (Details on the methodology are here.)

Rather than looking in aggregate at the Twitter patterns, the Gawker Media-owned website Jezebel called out by name and Twitter handle many of the individuals who had tweeted racist reactions to the President’s re-election, first with a gallery highlighting some of the tweets and then with a follow-up story, tracking down some of these users’ identities.

Specifically, Jezebel re-published the tweets, tracked down teens' locations and their schools, called those schools and then published the schools’ responses (or lack thereof). Jezebel co-founder Tracie Egan Morrisey writes,

“Many of those tweeters were teenagers whose public Twitter accounts feature their real names and advertise their participation in the sports programs at their respective high schools. Calls were placed to the principals and superintendents of those schools to find out how calling the president—or any person of color, for that matter—a “nigger” and a “monkey” jibes with their student conduct code of ethics.”

Responding to Jezebel's story, GigaOm’s Mathew Ingram questioned the decision to publish the teens’ names, asking when and if it’s okay to publicize this sort of “bad behavior” from teens:

“One of the things that troubles me about this incident is that it shows how quick we can be to judge a person — especially someone in high school, who may be acting badly for all kinds of complicated reasons — without any real understanding of what is going on, or what the repercussions may be. Making people face the consequences for saying things online is a noble goal, but is there no room even for children to make mistakes without the full force of the internet being brought to bear? As far as I can tell, Morrisey didn’t even try to contact the high-school students she profiled, or their parents.”

Internet Vigilantism

Ingram wonders if the condemnation and ridicule become too much — for teens in particular — when publicized online like this. (Jezebel gets about 3.6 million monthly readers to give you an idea of the reach of this story.) “When does it cross over into outright bullying?” he asks.

I’m not sure “bullying” is the right word here. To me, bullying involves the repetition of harassment. (That’s not to say that bullying won’t stem from this event, particularly now that names and schools are so public.) Rather, this strikes me as vigilantism, the topic of a recent danah boyd op-ed in Wired in which she observes the ways in which the Internet publicly “outs” people and proceeds to “tar and feather them.”

boyd argues that new technologies like Twitter magnify infractions and that this will in turn shape how we view and enforce justice (online, certainly, but with offline consequences as well). “In a networked society,” she writes, “who among us gets to decide where the moral boundaries lie?”

Surveillance, Souveillance, and Monitoring Teens Online

It’s hard not to view the listing of teens’ names, schools, and sports teams as appealing to the “justice” of the Internet -- indeed, the headline suggests the teens be "forced to answer" for their racist tweets. But by calling the teens’ principals and by invoking their various student handbooks, the Jezebel article also appeals to schools’ rules and Codes of Conduct. Internet justice meets institutional justice -- or something like that.

It’s hard not to view the listing of teens’ names, schools, and sports teams as appealing to the “justice” of the Internet -- indeed, the headline suggests the teens be "forced to answer" for their racist tweets. But by calling the teens’ principals and by invoking their various student handbooks, the Jezebel article also appeals to schools’ rules and Codes of Conduct. Internet justice meets institutional justice -- or something like that.

But appealing to the schools to intervene here raises lots of questions about social media surveillance of students as well. What role and responsibility — legally, ethically — should schools take in monitoring students’ speech online (specifically online but off campus)? And what are the consequences for students as students when they've committed an infraction online?

To expand on boyd’s question above, we can ask, “In a networked society, who among us gets to decide if teens have violated moral boundaries?” And what then? This isn’t a question for just parents or peers. Clearly it isn’t one just for schools.

And what are the consequences for teens — all teens, not just those who tweeted something racist on Tuesday night — learning to negotiate society’s moral boundaries as they grow up into it, all the while learning to negotiate this in public?