Building an Student Data Infrastructure

The Shared Learning Collaborative, a Gates Foundation-funded initiative, rebranded itself this week. There’s a new name — inBloom, Inc. — but the mission and plans remain the same, the new non-profit insists.

That mission is to build an open source, cloud-based education data infrastructure in the hopes of addressing a number of problems schools face: the lack of data interoperability between the various databases and software systems that they utilize and the merits of spending money to update outdated administrative IT (versus, say, buying instructional — or other — tech and/or versus spending money on something altogether non-tech).

While we’re seeing an explosion in the number of technology tools that schools utilize (hardware, software, apps, the Web), these tend not to “talk” to one another nor to the student information systems that store students’ education records. That makes for a lot of bureaucratic inefficiencies with teachers and staff manually downloading, uploading, re-entering student information — rosters, grades, and so on — into various applications. All this also means that it’s difficult to build a full profile on students and to track and support their progress.

The latter is of increasing interest to schools and to states and to service providers, particularly now that education is supposed to be more “data driven.”

Concerns about Sharing and Storing Student Data

“Data driven” — that’s code for more standardized testing, some folks fear. More testing, more hiring and firing of teachers based on testing, more surveillance. In that light, it’s no surprise that the Shared Learning Collaborative — now iBloom — has faced some pushback from those who link it to corporate education reform, After all, it’s a project with some $100 million in funding from the Gates and Carnegie Foundations and built (in part) by News Corp-owned Wireless Generation, with a new CEO who comes from Promethean, maker of interactive whiteboards.

A number of organizations — the Massachusetts ACLU, the Massachusetts state PTA, the Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood, Class Size Matters, and others — have expressed their concerns about the project, arguing that the initiative will have schools sharing “confidential student and teacher information with the Gates Foundation. The information to be shared will likely include student names, test scores, grades, disciplinary and attendance records, special education and free lunch status.” According to Leonie Haimson, executive director of the NYC organization Class Size Matters, this data grab by the Shared Learning Collaborative — now inBloom — is “unprecedented.”

Haimson contends that this initiative, currently being piloted in 9 states (Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, and North Carolina), has been undertaken without parental consent and furthermore will open access to students’ data to third-party vendors, again, without parental consent. “‘Open access,’ ‘open source’ and ‘open this’ and ‘open that,’” Haimson told me in a phone interview on Friday, suggesting that the interest in student data was more about “opening for business” and appealing to startups than it was addressing a demand by teachers or parents.

Haimson also cites concerns about privacy and security in the cloud, as schools move their data storage and servers from a local to a virtualized environment, pointing to inBloom’s privacy and security policies that state that the company “cannot guarantee the security of the information stored in inBloom or that the information will not be intercepted when it is being transmitted.” “I wonder if NY state and the other states involved realize that they may be vulnerable for multi-million dollar class action lawsuits if and when this highly sensitive data leaks out,” Haimson wrote in a recent blog post, “especially since Gates and inBloom appear to have disclaimed all responsibility for its safety.”

But Sharren Bates, the Chief Product Officer for inBloom, insists that “of course, data privacy and security are our number one concern.” InBloom’s infrastructure and the access it affords to student data is FERPA compliant, and there are rigorous security procedures in place, including encryption, to protect data from theft or tampering.

(It’s worth noting here, I think, that no system is completely secure, and schools — whether they store their data in local servers or in the cloud — are already quite vulnerable to data breaches. And remember too: one of the biggest hacking stories of last year — the near erasure of Wired reporter Mat Honan’s entire digital life — was as much a matter of social engineering than it was any failed technical security measures.)

With the inBloom infrastructure, schools and states do get to control who has access to the data that’s stored and transmitted, as well as what type of access is granted. Someone in the role of “teacher,” for example, will be able to see the data of the students in her or his class and be able to update assessment and assignment information; someone in the role of “principal” will be able to see the data of the students in her or his school, but not be able to update assessment or assignment information; a district or state-level “super administrator” will be able to determine which third-party application providers can connect to the infrastructure and what information they can access.

Better Data Privacy, Security and Transparency

Fact of the matter, third-party providers — websites, games, textbooks, assessment tools, learning management systems, magazines, email, search engines, student information systems, social networks — already have a lot of student data. And that student data isn’t simply name, grade level, date of birth, grades, and/or attendance dates that we've long construed as part of the FERPA-protected "education record." Student data now includes the “data exhaust” we increasingly leave behind when we use computer-based applications — our queries, our location (via GPS or RFID), our length of time on a task or on a site, our keystroke patterns, our networked relationships.

Many companies hoard this data — particularly the incumbents in the industry, particularly those that are hoping that big data will be "the new oil." To unlock the full potential of learning analytics, we must unlock the data.

inBloom says that it’s mission is to help schools and teachers tap into all of this data: “Better, more integrated technology and data analytics can help by painting a more complete picture of student learning and making it easier to find learning materials that match each student’s learning needs. Unfortunately, creating the technology infrastructure to do this is often too expensive for most states and school districts.”

While “personalized learning” may be the stated goal of inBloom, it’s easy to see that this sort of data infrastructure can (and will) also be used to enable surveillance — monitoring and assessing students and in turn teachers and in turn schools. (Once again: “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral” — Kranzberg’s first law of technology)

But such are the trade-offs we are increasingly making when it comes to living (and learning) in a digital world: to fully participate in it, to reap the (purported) benefits, we find ourselves giving up our privacy — or at least we give up control of a lot of our data. It's a matter of both consent and coercion.

That is, we hand over our data with varying levels of informed consent — we do so begrudgingly and willingly and unconsciously. We do that, we adults. And as such we must ask how well we help children make choices about their own data — ownership and privacy. We must consider what decisions we make — as parents, teachers, schools, app-makers — on their behalf. We must weigh when and why control over data rests with the institution (with schools, with districts) and when it rests with the app-maker (the big companies and the little startups) and when it rests with the individual.

Along with questions about privacy and security of student data, then, and the demands we do our best to protest these, should be questions about and demands for transparency. Who controls education data and to what end? What data? Can a student (or parent), as FERPA outlines, request access to review and amend her data? (All her data.) And (even better) can she control it herself?

The data infrastructure being built by inBloom doesn’t necessarily answer any of these questions. It might revolve some; it might exacerbate others. Such are the politics of education data, if you will. The non-profit has said, however, that it intends to make its technology open source. It remains to be seen if this will be sufficient so that it can be leveraged by schools and teachers and the students themselves for the students themselves — and if a more efficient data infrastructure doesn't exist simply to "spur innovation," which is too often code for generating sales among third party ed-tech providers.

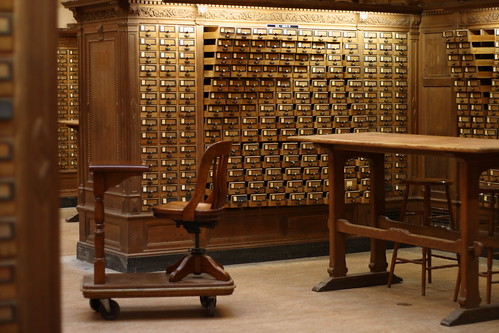

Image credits: Sage Ross