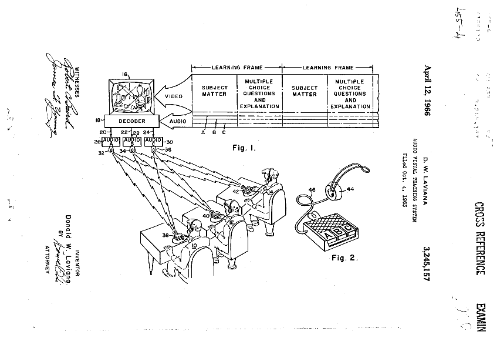

Mike Caulfield tweeted this picture this morning, with a wry chuckle alluding to MOOCs' pretension that they've invented this whole ed-tech thing: a 1966 patent for an “audio visual teaching system.”

The tweet fits nicely with a project we're working on: trying to uncover and document some of the “hidden history” of ed-tech (and it dovetails too with my forthcoming book on Teaching Machines).

The History of Ed-Tech (As Told Through Patents)

Looking at the various education technologies that have been patented over the years is a pretty fascinating exercise. (If you’re curious, you can search Google or the US patent office.)

Patents, of course, are designed to guard the intellectual property of the inventor, so that that person in turn can exclude others from developing or selling the invention. As such, education patents are interesting not only for what they can reveal about intellectual history, commercial interests, and legal machinations, but for what they demonstrate about our conceptions of teaching, learning, and technology.

And technology is the point, of course, of the patent. The UN’s World Intellectual Property Organization defines an invention eligible for patenting as “a solution to a specific problem in the field of technology. An invention may relate to a product or a process.” Education patents, in other words, offer technological “solutions” to the “problems” of teaching or learning, and those problems are by definition technological. Patents, that means, aren't simply "technical"; they're ideological.

A Sampling of Education Patents

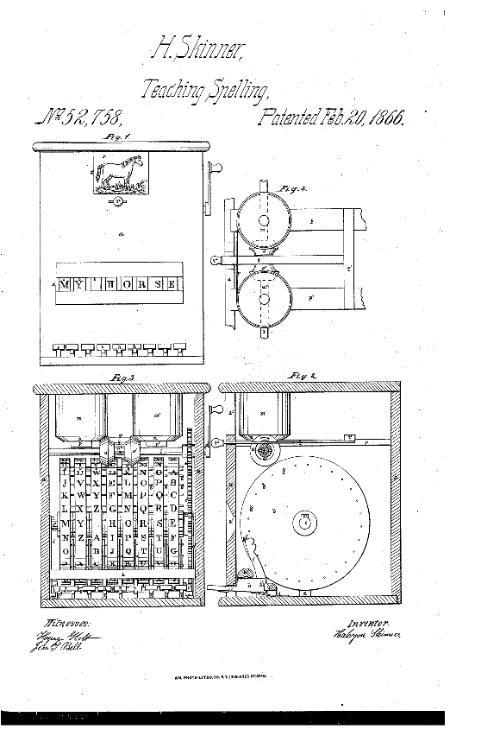

Apparatus for teaching spelling (1866) (Link)

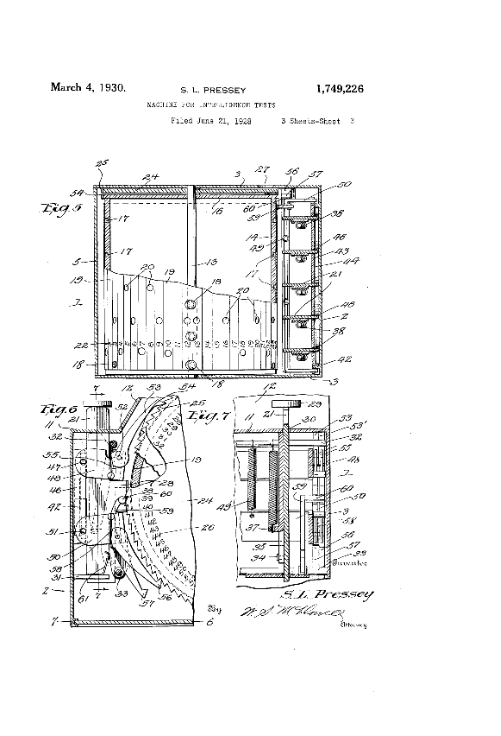

Machine for intelligence tests (1928) (Link)

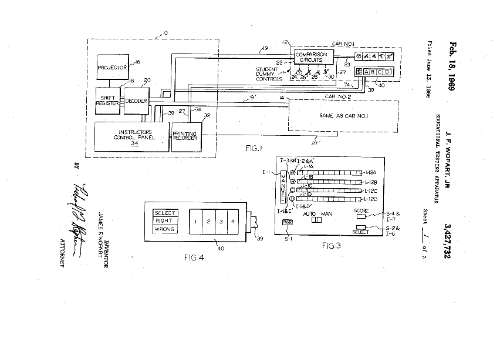

Teaching and testing aid (1957) (Link)

Skinner! Dude! You weren't even first!

Educational testing apparatus (1966) (Link)

Networked education and entertainment technology (application, 2011) (Link)

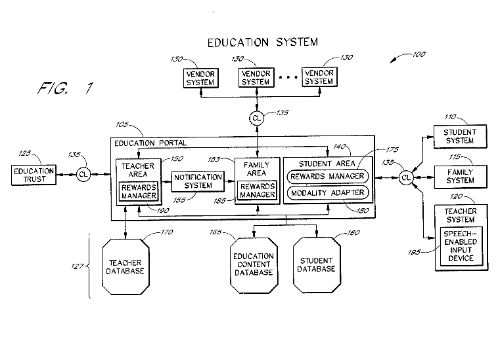

Education system and method for providing educational exercises and establishing an educational fund (1999) (Link)

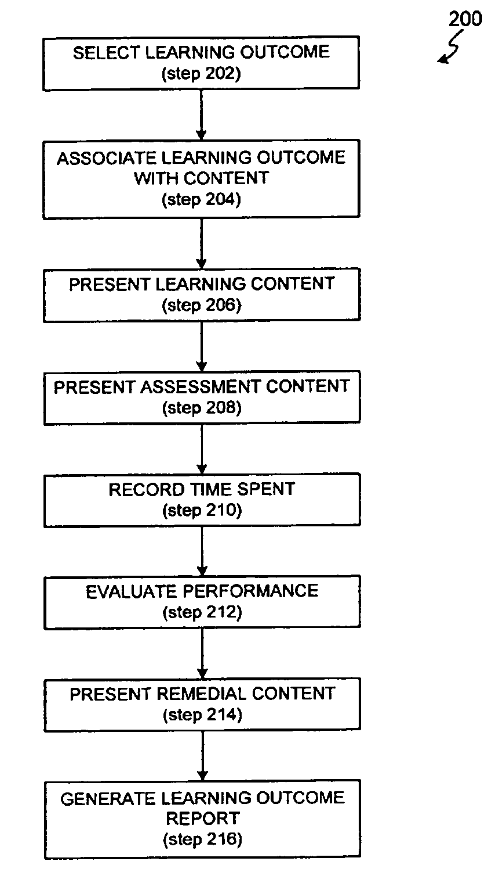

Learning outcome manager (2005) (Link)

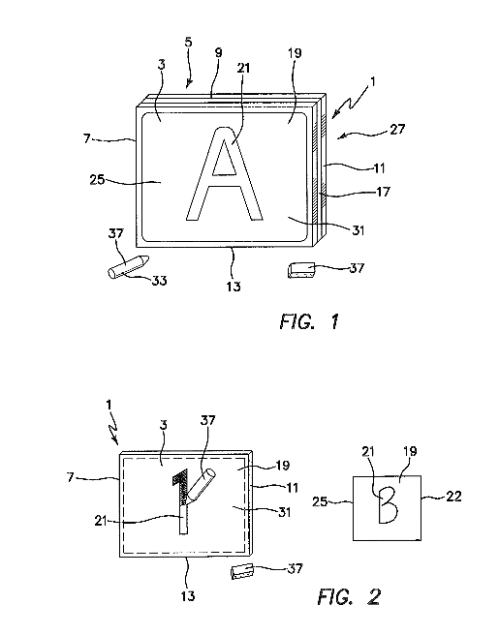

Multi-sensory education device (application, 2007) (Link)

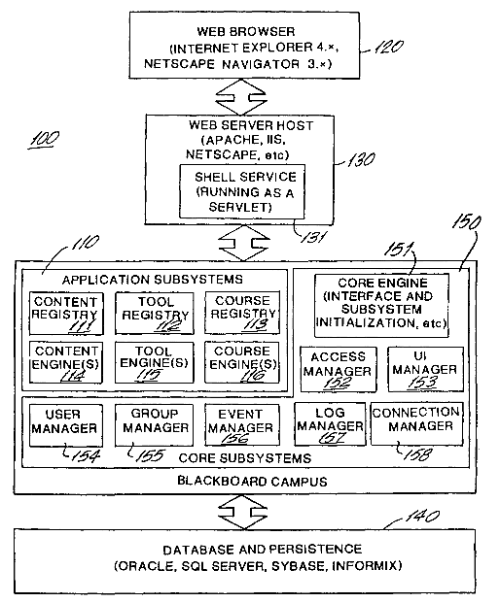

Internet-based education support system and methods (1999) (Link)

This is an important one. It’s Blackboard’s patent for the LMS that it used in 2006 to sue its competitor Desire2Learn for infringement – a case that D2L eventually won. That legal battle left a bitter taste in many education technologists’ mouths, cementing Blackboard’s negative image in certain circles. (I mean, beyond the whole “wow, this LMS thing is crap” response.)

That lawsuit prompted an initiative to document, on Wikipedia, some of the longer history of “virtual learning environments” (yet another reason why this "hidden history" matters) – that is, to demonstrate the “prior art” that would challenge Blackboard’s claim to having invented "the product," "the process."

And that is, indeed, part of the problem with the current intellectual property regime. “The patent system is broken,” as EFF puts it. Patents, which can be bought and sold, are increasingly wielded to stave off competition (and often to shake down smaller, newer companies); and thus, patents can serve to impede innovation rather than encourage it.

Ed-Tech Patents and "The Inventive Step"

But the problem lies too in demonstrating (or in the case of the US Patent and Trademark Office, assessing) the “inventive step” necessary for a patent to be granted. It’s a practical question when it comes to patent application; but it’s an interesting epistemological question too: what counts as as “inventive.” What counts as “new”? (Conversely, what's not new? What beliefs and practices are carried forward?) What counts as “innovation” in education? What does it mean to have that framed in terms of technological methods? Or, by definition (if we use the definition of WIPO, that is), must innovation be technological?

And see, how quickly we come to the narratives and the ideology, and not just the inventions, that inform the history of ed-tech.