“Television came to American Samoa on Sunday afternoon, October 4, 1964.” Thus opens a 1981 book by mass communications scholar William Schramm and his colleagues, Bold Experiment: The Story of Educational Television in American Society. Although there were other instructional television initiatives ongoing around the world, its introduction in American Samoa “was the first time a developing region set out to use that medium in an all-out attempt to modernize an educational system.”

Four years later, after visiting a school in American Samoa, President Lyndon Johnson declared “the bold experiment” a success:

“Samoan children are learning twice as fast as they once did, and retaining what they learn. Surely from among them, one day, will come scientists and writers to give their talents to Samoa, to America, and to the world.”

But in the following years, there grew a substantial resistance and resentment to this centralized system of televised instruction – from teachers and from students, particularly at the high school level. (Perhaps there had been earlier too, but data on teachers’ and students’ attitudes, as well as on students’ educational attainment was not tracked in the initiative’s early years.) By 1979, Schramm reports, the broadcasts had been radically trimmed – from a studio system that produced 6000 educational programs a year to one that produced just one series. Instead of supplanting teachers, “television’s classroom role had been largely reduced to that of a supplemental or enrichment service, to be used when and if a teacher decided it was appropriate.”

Television didn’t go away, of course. But the transmissions became commercial – carrying NBC (and some PBS) programming. (The two most popular shows in American Samoa in 1976: Police Woman and Sanford & Son.)

Coming of the Kennedy Administration in Samoa

The United States took control of the eastern Samoan islands at the turn of the century, following the Tripartite Convention of 1899 that split Samoa into two parts. American Samoa remains an unincorporated US territory. In the 1950, the jurisdiction of the territory was handed over by the US Navy to the Department of the Interior, and until 1978, the governor was a presidential appointment. Rarely did those appointed stay in office longer than a year or two.

In 1961, the Kennedy administration appointed H. Rex Lee governor. He served from May 1961 to July 1967 and again from May 1977 to January 1978, appointed by President Carter to help with the transition of the territory to an elected executive branch. In those intervening years, he served as the commissioner of the FCC.

He was a believer in television.

Lee said in 1966, “I was not only intrigued with what television might do for our children and teachers, but I also was convinced that it would be a useful tool in working with the community as a whole – a community that was grossly undereducated but one that America needed to bring into the 20th century in a hurry.” His daughter had learned to type while watching an instruction television show and had then landed a job. He’d taken a television course on conversational French. Lee believed that television would be the key to modernizing American Samoa’s education system.

American Samoa’s School System

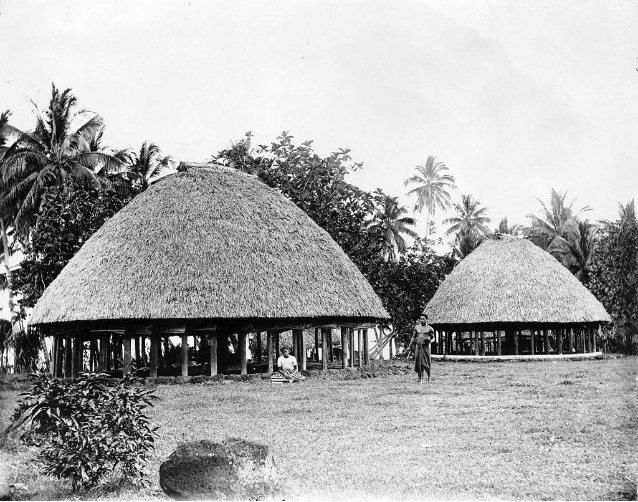

When Lee arrived in American Samoa, its education system was, in Schramm’s words “a shambles, literally in terms of facilities and figuratively in terms of educational standards and results.” Most of the elementary schools were one room fales, traditional wall-less structures with wooden posts holding up domed, thatched roofs. There was not enough space in the high schools to accommodate all the students who graduated from the elementary level. Annual expenditure per pupil expenditure for the 1959–60 school year was $50. (The average on the mainland:$487.) Furthermore, the teachers themselves had limited training. Not a single one had a mainland teaching certificate, and the Gates Reading Survey in 1967 found that elementary school teachers were only barely reading at a level higher than their students.

When there were educational materials available for classes, often they were were “hand-me-down mainland textbooks that had been discarded as out-of-date,” Schramm noted.

Samoan children read about snow, railroads, highways, and great cities with tall buildings. All this in a climate where the temperature rarely drops below 75°F, where there is nothing that faintly resembles a railroad, and where an occasional two-story building towers above the native houses. The world of Dick and Jane, in short, had little relevance to the Samoan youngsters.

While most students spoke Samoan at home, there were pressures – as well as promises from the administration – for English-language learning. At the same time, there were ongoing concerns about how the education system would support or undermine the traditional Samoan culture.

Recommending the Move to Educational Television

Governor Lee asked Congress for $40,000 for a “feasibility study” to see if educational television could be used to “fix” the Samoan education system. His request was granted, and Lee approached the National Association of Educational Broadcasters to conduct it.

The NAEB team visited American Samoa in 1961 and issued their report in January 1962 recommending that television be made the major form of instruction. But they also recommended that the entire educational system be revamped – they suggested that schools be reorganized so that elementary schools covered grades 1–8 and high schools focused on 9–12; they urged a new curriculum, one that was “relevant to Samoa and to its customs and people”; they recommended that English be taught as a second language, so that literacy and comprehension in Samoan was attained first.

With respect to television, the report recommended that the “new curriculum” should be in the planning for at least a year before the changeover. In the way of equipment and staff, it recommended the construction of a six-channel VHF television station operating through transmitters located atop Mount Alava, Tutuila’s second-highest mountain; the establishment of a four-studio production center capable of turning out approximately 200 television lessons each week, complete with lesson guides, worksheets, tests, and materials; and the recruitment of approximately 150 curriculum specialists, engineers, and principals, along with television and research teachers, producers, artists, photographers, and printers."

A budget request of $2,579,000 for a television system and $3,173,750 for construction of new schools was made for fiscal 1963, which Congress approved in almost its entirely (providing $1,000,000 less for the TV system).

No other method of improving the Samoan education system – better training of its teachers, replacing those teachers with American ones – was ever really considered.

“There was no time for waiting, no time for armchair patient – there had been too much of that for sixty years,” Governor Lee said. The television system was built rapidly – a process that had to include wiring some remote places for electricity. The curriculum was developed rapidly as well. 26 new schools were also under construction (many of which kept the fale architecture but contained two areas with a wall dividing them, where a 23" television was installed), although when KVZK-TV went on the air in October 1964, only four of them were complete.

Classroom and Telecast Schedule, Level 4 (Grades 7 and 8), September 1965

- 7:30–7:40 Opening exercises

- 7:40–7:50 Study period

- 7:50–8:00 Preparing for mathematics

- 8:00–8:20 Mathematics telecast

- 8:20–8:45 Follow-up mathematics

- 8:45–8:50 Preparing for sound drill and oral English

- 8:50–9:10 Sound drill and oral English telecast

- 9:10–9:15 Preparing for language arts

- 9:15–9:35 Language arts telecast

- 9:35–10:15 Preparing for science (MWF) / Preparing for hygiene and sanitation (TTh)

- 10:15–10:35 Science or hygiene and sanitation telecast

- 10:35–11:00 Follow-up for science or hygiene and sanitation

- 11:00–11:05 Preparing for physical education

- 11:05–11:30 Physical education activities (telecast 11:05–11:20 M)

- 11:30–11:40 Wash hands

- 11:40–11:45 Preparing for oral English

- 11:45–12:00 Oral English telecast

- 12:00–12:30 Lunch

- 12:30–12:40 Preparing for social studies

- 12:40–1:00 Social studies telecast (MWF) / Fa’alogo Ma Aoa, a show-and-tell program (TTh)

- 1:00–1:30 Follow-up for social studies; evaluation and dismissal

- 1:45–3:00 In-service for teachers, telecast 2:00

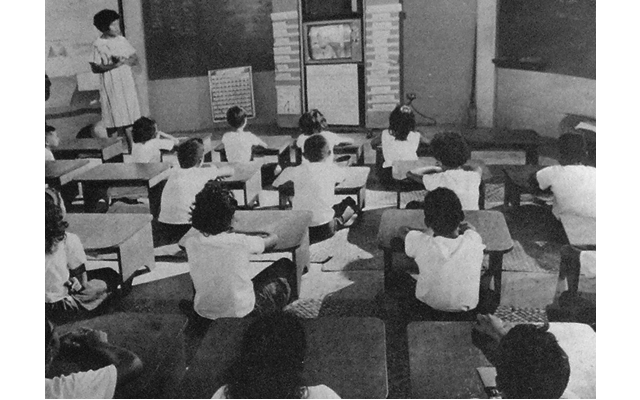

Students across all grade levels spent about one-third of their day watching television.

During the first years of the system, approximately 170 programs were produced locally each week, representing 53.5 hours of air time and some 180 hours of studio time. All programs intended for use in the schools were prerecorded and broadcast from videotape. After the first year, the weekly television schedule was augmented with the use of the videotapes of 51 school programs (mostly language drills) from the preceding year. This represented a weekly output of 221 instructional programs, or about 61.25 hours.

The station also broadcast two to four in-service programs each week, varying in length from 30 minutes to one hour, plus four to six hours of evening programming six nights a week, which normally included six to eight different local programs, totally approximately three hours. The station was thus responsible for about 88 hours of programming a week, two thirds of which was new production. Looked at in another framework, the instructional programming alone amounted to more than 6,100 telecasts a year, or about 2,000 hours of air time. In comparison, not even the largest U.S. commercial stations of the day produced local programs at anything like this rate.

But the quantity of programming - and the rapidity of the roll-out - came at the expense of quality, as the studio teachers were responsible for creating 10 to 15 programs per week. Each television lesson came with directions for the Samoan classroom teachers, who were told precisely what to do to prepare for each lesson, what to do during the broadcast, and what to say afterwards. As Schramm points out, “although students spent only about two hours of each school day actually watching the screen, all instruction revolved around the broadcast curriculum.” There were supposed to be supplementary worksheets that came with each broadcast, but often these did not reach a classroom until long after the lesson had been shown.

Teachers, no surprise, were frustrated by the lack of control over their classrooms – this centralized system had replaced one that was most often managed at the individual village level. Teachers argued that the strict broadcast schedule meant they could not deviate, even if their students needed or wanted to spend more time on a topic.

There were also problems because, contrary to the NAEB’s initial recommendations, the emphasis was not on English as a second language but on Samoan – the students’ native language – as the second language. Most of the studio teachers came from the mainland, and the curriculum presupposed that English was the language of instruction after the third grade. This made it particularly challenging to craft lessons in other subject areas as students had a very limited English vocabulary. As Schramm observes, “In effect, what this meant was that no teacher of any subject, at any grade level, could use words or phrases in his or her instruction that had not already been introduced in the English language course at that grade level. It made an already inflexible system still more inflexible and introduced a requirement that many television teachers later were to find seriously inhibiting in their subject areas.”

A survey of teachers and students conducted in 1972 found that the higher the grade level, the more the attitudes towards educational television declined. 70.6% of fifth graders, for example, said they learned better with educational television, but just 23.5% of twelfth graders said that. (It’s important to note that 1972 was the first time that students and teachers were systematically asked for their opinions on the initiative, and it’s hard to see if the growing dissatisfaction and disillusionment with educational television could have been addressed better –or at least differently – if it had been addressed earlier.)

In 1973, policy makers decreed that teachers, principals, and students should participate in the course planning process; moreover teachers should have control over whether or not they used a television lesson. Over the next few years, television – both the production of lessons and their use in the classroom – was cut further and further back. By 1975, high schools were not using instructional television at all. KVZK was separated from the Department of Education in 1976. (It’s still on air today – a local PBS station.)

Despite the excitement about the initiative in its early years and despite the endorsement of President Johnson, educational television in American Samoa was hardly an overwhelming success. But nor was it an utter failure, at least by Schramm’s assessment. They piece together some of the various test scores from the islands – again a problem since there was no baseline against which to compare the impact of educational television, concluding “There is nothing in this evidence to say television succeeded or failed, except that it did not accomplish the expected miracle.”

Excitement about the possibility of educational television as a “modernization” effort did, Schramm argues, serve to convince Congress to increase the amount of money spent on the Samoan education system: from $50 per pupil in 1961 to $1041 per pupil in 1980 when Schramm’s book was published. Still today, however, the per pupil expenditure for students in American Samoa remains the lowest of all states and territories. ($3,826 in 2007, which is the last year I can find the data on the NCES website.)

The rejection of educational television wasn’t a rejection of the technology. But it was at the very least, a rejection of too much technology, a rejection of the centralized control over curriculum and instruction, and a rejection of the insistence from mainland administrators and ed-tech proponents that a change to the educational system occur rapidly, with no input from teachers or students.