This is the transcript of the talk I gave this evening at the CUNY Graduate Center

Thank you very much for inviting me to speak to you. We’re nearing the end of the semester, I think, and so we’re all exhausted. (Or I should speak for myself: I’m exhausted.) For me, the end of the school year also means the end of a year-long fellowship I’ve had at the Columbia School of Journalism. I’ve decided to stick around New York for a while longer, so I hope this is just the first of many opportunities to interact with you all here. (Indeed, I’ll be speaking again in CUNY next week.)

I do want to talk a little bit this evening about the work I’ve been doing as a Spencer Fellow. That’s not what it says in my title and abstract, I recognize. And that’s the curse of making up titles and abstracts in advance: sometimes you sit down to prepare a talk and realize you really want to say something else entirely, and so your task becomes trying to thread things all together so that no one who shows up expressly to hear you expand on the ideas advertised on the flyer is too frustrated or disappointed.

And the flyer for this talk, I do want to note, was really great. So I’ll start there and see if I can weave all these advertised and unadvertised end-of-semester ideas together somewhat satisfactorily.

(Including an obligatory reference to pigeons.)

I love old teaching machines, yes even BF Skinner’s teaching machines, despite their deeply problematic usage. I love them, in part, because they are objects. These objects carry a history. They reflect an ideology. They have substance. They have weight – literally, culturally, intellectually, politically. They are material artifacts, and we can talk about how they were made, how they were manufactured. And that seems particularly important, that materiality. It helps us see design and functionality and production and history and even ideology in ways that I think today’s digital teaching machines and teaching machine-makers are more than happy to obscure.

Chris Gilliard recently wrote an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education in which he invoked the story of “the Mechanical Turk,” designed by Wolfgang von Kempelen in the late 1700s – an automaton that purported to play chess, but in truth, was a hoax. Hidden inside the mechanical device was a human chess master who actually operated it, “his invisible labor controlling the Mechanical Turk’s movements.” Gilliard contends that the invisible labor of students powers today’s teaching machines. We are repeatedly told these (ostensibly) delightful stories of the magical powers of artificial intelligence and learning analytics and instructional software. But maybe all this is just another parlor trick, another hoax – an exploitation that is obscured, Gilliard argues as I’d argue, because it’s much harder now than it was with von Kempelen’s automaton, to pull back the curtain, to follow the wires and levers, to comprehend the engineering, and to see the “ruse” of the teaching machine.

“Personalization” – that’s the illusion created by the teaching machine. It has been the illusion, the intent for a very, very long time.

I’m really interested in that history. And I think, in some ways, we can point to the history easier than we can point to the code that runs the thing.

I’m also interested in the contemporary stories we hear about “personalization,” partly out of a frustration that the tech sector always seems to want to obscure and ignore history.

But ah, the tech sector does love stories – grand narratives and make-believe and mythologies about “revolution” and “disruption” and ’innovation." I’m deeply curious (and quite suspicious) about where these narratives come from and how they’re spread among education technology entrepreneurs and investors (and – this is so key – among politicians and school administrators).

That’s been the focus of my Spencer Fellowship work this year. I proposed a project that would investigate how the investor networks operate in education technology – who is doing the funding, what they’re funding, of course, but also how investors know about what and who to fund. That is, how do investors get their ideas about education technology (and of course, about education reform)? What are the stories they hear and they tell about the future (and the past)? How do they use their networks to spread ideas (and, of course, to build businesses and to change policies and to sway markets and to shape public opinion)?

Now, Silicon Valley famously insists, “we don’t invest in ideas; we invest in people.” But it’s ridiculous to assert that ideas – and ideology – are irrelevant in investors’ calculations. Ideas matter. Ideas matter, as do the networks they’re embodied in.

So, I’ve been looking for “The Ed-Tech Mafia,” I have sometimes called this – a nod to “The PayPal Mafia,” a phrase coined to describe those early employees and executives at PayPal who’ve gone on to shape recent Silicon Valley history and politics and business (and tech industry culture – “brotopia” as journalist Emily Chang has called it), as investors and as entrepreneurs. Reid Hoffman, the founder of LinkedIn. Elon Musk, the founder of Tesla and SpaceX. Peter Thiel, Facebook board member, founder of Palantir, and enemy of the free press who famously paid a handful of young people – mostly men – $100,000 to drop out of college. Chad Hurley, the founder of YouTube. Pierre Omidyar, the founder of eBay. And so on. Men – and it is all men, in this case – men of ideas, libertarian ideas, ideas about “innovation” but also about public institutions and public space and governmental regulation and private finance and data and surveillance and control.

My question (or one of my questions): is there an organization or a company in education that has had similar clout – launching the careers of entrepreneurs and investors, obviously, but also setting the agenda for what “the future of education” (and the future of education as a market, the future of education as “the business of education”) looks like. Last week, I was at the particularly dreadful ASU+GSV Summit where these people all gather every year to build networks, make deals, shape policy, and tell stories. Tell tall tales, I’d even say, about the coming revolution in education.

That “revolution” has been associated with many buzzwords over the years. “MOOCs” for a while. “Social learning.” Social emotional learning. Behavior management and behavior modification. Personalization.

All of these are positioned and invoked in opposition to some imagined or invented version of learning in the present or in the past. Education technologists and futurists (and pundits and politicians) like to provide these thumbnail sketches about what schooling has been like – unchanged for hundreds or thousands of years, some people (who are clearly not education historians) will try to convince you. They do so in order to make a particular point about their vision for what learning should be like. “The factory model of education” – this is the most common one – serves as a rhetorical and political foil against which reforms and technological interventions can be positioned. These sorts of sketches and catchphrases never capture the complex history of educational practices or institutions. (They’re not meant to. They’re slogans, not scholarship.) Nevertheless these imagined histories are often quite central to the premise that education technology is different and disruptive and new and, above all, necessary.

There is no readily agreed upon meaning of the phrase “personalized learning,” which probably helps its proponents wield these popularized tales about the history of education and then in turn laud it – “personalized learning,” whatever that is – as an exciting, new corrective to the ways they claim education has “traditionally” functioned (and in their estimation, of course, has failed).

“Personalized learning” most often means that students “move at their own pace” through lessons and assignments – unlike those classrooms where everyone is expected to move through material together, like the students in a certain Pink Floyd movie. (In an invented history of education, this has been the instructional arrangement for all of human history.) Or “personalized learning” can mean that students have a say in what they learn – students determine topics they study and activities they undertake. “Personalized learning,” according to some definitions, is driven by students’ own interests and inquiry rather than by the demands or standards imposed by the instructor, the school, the state. “Personalized learning,” according to other definitions, is driven by students’ varied abilities or needs; it’s a way of navigating the requirements of school bureaucracies and requesting appropriate accommodations – “individualized education plans” and the like. Or “personalized learning” is the latest and greatest – some new endeavor that will be achieved, not through human attention or agency or through paperwork or policy but through computing technologies. That is, through monitoring and feedback, through automated assessment, through data mining, and through the programmatic or algorithmic selection and presentation of new or next materials to study.

“Personalized learning,” depending on how you define it, dates back to Rousseau. Or it dates back further still – to Alexander the Great’s tutor, some guy named Aristotle. It dates to the nineteenth century. Or to the twentieth century. It dates to the rise of progressive education theorists and practitioners. To John Dewey. Or to Maria Montessori (often the only woman ever mentioned in any of these tales). Or it dates to the rise of educational psychology. To B. F. Skinner. To Benjamin Bloom. It dates to special education-related legislation passed in the 1970s or to the laws passed the 1990s. Or it dates to computer scientist Alan Kay’s 1972 essay “A Personal Computer for Children of All Ages.” Or it dates to the Gates Foundation’s funding grants and political advocacy in the early 2000s. Take your pick. (And when you take your pick, know that it likely reveals your education politics and, I’d argue, your education networks.)

According to the flyer, I’m supposed to talk to you today about the history of personalized learning and how “automation” became “personalization.” And I want to do so. I want to do so because I want us to remember the Mechanical Turk. I want to do so because “personalized learning” has taken on such political and financial and rhetorical significance. Personalized learning has become incredibly bound up in Silicon Valley’s philanthro-venture-capitalism and in its plans for shaping the future of education (and shaping it with machines). Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, for example, are plowing billions of dollars into “personalized learning” products and school reforms. That seems significant – not only if we don’t agree on what the phrase actually means, but also if it means something along the lines of Facebook, knowing what Facebook has done to information sharing and to civic understanding.

In some ways, this is the challenge of tracing the history of ed-tech. There are multiple histories, origins, and trajectories – in no small part because so many of today’s ed-tech business folks believe in invented histories, in part because some of this taps into cultural and pedagogical practices that are so familiar we just don’t see them. The Mechanical Turk – we prefer the parlor trick.

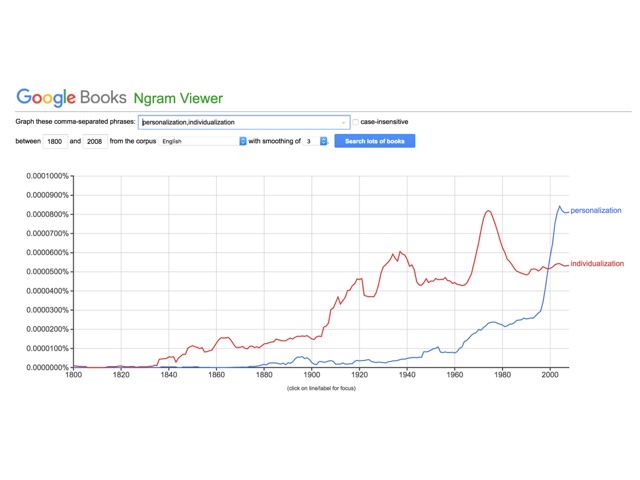

The OED dates the word “personalization” in print to the 1860s, but the definition that’s commonly used today – “The action of making something personal, or focused on or concerned with a certain individual or individuals; emphasis on or attention to individual persons or personal details” – dates to the turn of the twentieth century, to 1903 to be precise. “Individualization,” according to the OED, is much older; its first appearance in print was in 1746.

The Google Ngram Viewer, which is also based on material in print, suggests the frequency of these two terms’ usage – “individualization” and “personalization” – looks something like this:

In the late twentieth century, talk of “individualization” gave way to “personalization.” Why did our language shift? What happened circa 1995? (I wonder.)

Now, no doubt, individualism has been a core tenet of the modern era. It’s deeply enmeshed in Western history (and in American culture and identity in particular). I always find myself apologizing at some point that my talks are so deeply US-centric. But I contend you cannot analyze digital technologies and the business and politics of networks and computers without discussing how deeply embedded they are in what I’ve called the “Silicon Valley narrative” and in what others have labeled the “California ideology” – and that’s an ideology that draws heavily on radical individualism and on libertarianism.

It’s also an ideology – this “Silicon Valley narrative” – that is deeply intertwined with capitalism – contemporary capitalism, late-stage capitalism, global capitalism, venture capitalism, surveillance capitalism, whatever you prefer to call it.

Indeed, we can see “personalization” as both a product (and I mean quite literally a product) of and a response to the rise of post-war consumer capitalism. Monograms on mass-produced objects. Millions of towels and t-shirts and trucks and tchotchkes that are all identical except you can buy one with your name or your initials printed on it. “Personalization” acts as some sort of psychological balm, perhaps, to standardization.

A salve. Not a solution.

But “personalization” is not simply how we cope with our desire for individuality in an age of mass production, of course. It’s increasingly how we’re sold things. It’s how we are profiled, how we are segmented, how we are advertised to.

Here’s Wikipedia’s introduction to its entry on “personalization,” which I offer not because it’s definitive in any way but because it’s such a perfect encapsulation of how Internet culture sees itself, sees its history, tells its story, rationalizes its existence, frames its future:

Personalization, sometimes known as customization, consists of tailoring a service or product to accommodate specific individuals, sometimes tied to groups or segments of individuals. A wide variety of organizations use personalization to improve customer satisfaction, digital sales conversion, marketing results, branding, and improved website metrics, as well as for advertising.

How much of “personalized learning” as imagined and built and sold by tech companies is precisely this: metrics, marketing, conversion rates, customer satisfaction? (They just use different words, of course: “outcomes-based learning,” “learning analytics.”)

Online, “personalization” is how we – we the user and we the consumer – are convinced to take certain actions, buy certain products, click on certain buttons, see certain information (that is to say, learn certain things). “Personalization” is facilitated by the pervasive collection of data, which is used to profile and segment us. We enable this both by creating so much data (often unwittingly) and surrendering so much data (often voluntarily) when we use new, digital technologies.

“The personal computer” and such. (You know it’s “personal.” You get to change the background image. It’s “personalized,” just like that Coke bottle.)

The personal computer first emerged as a consumer product in the 1970s – decades after educational technologists and educational psychologists had argued that machines could “personalize” (or at the time, “individualize”) education.

And let me pause here to return briefly to that topic of “the ed-tech mafia.” Because education technology – and the business of education technology – is not a new phenomenon. And those who have developed that business – that network of entrepreneurs and investors – were not simply those in Silicon Valley. And they weren’t just in business. They were academics. The field of education technology emerged from the field of educational psychology. It emerged from the work of scholars at Harvard, Columbia, Stanford. That network.

Efforts to personalize education through technology are, in fact, about a century old. And this history matters. It matters in the materiality of the machine. It matters in the networks of men – yup, mostly men – propagating the idea. It matters in the beliefs and practices that the technologies have encouraged and embedded in schools.

Over Spring Break, I took a trip to Columbus, Ohio where I visited the archives of Sidney Pressey, a psychology professor at Ohio State University from 1921 to 1959 (he continued to publish papers until his death in 1979). (I should note here that Ohio State in the 1920s was seen as one of the leaders in psychology, alongside Columbia and Stanford.) Pressey studied at Harvard under Robert Yerkes, who of course helped design the Army Alpha tests to millions of military recruits in World War I – the first large-scale administration of intelligence testing (standardized testing) in the US. Another Harvard figure, BF Skinner, is often credited with inventing the teaching machine. But it was Sidney Pressey who, decades before, assembled a prototype out of typewriter parts and demo-ed it at the 1924 meeting of the American Psychological Association.

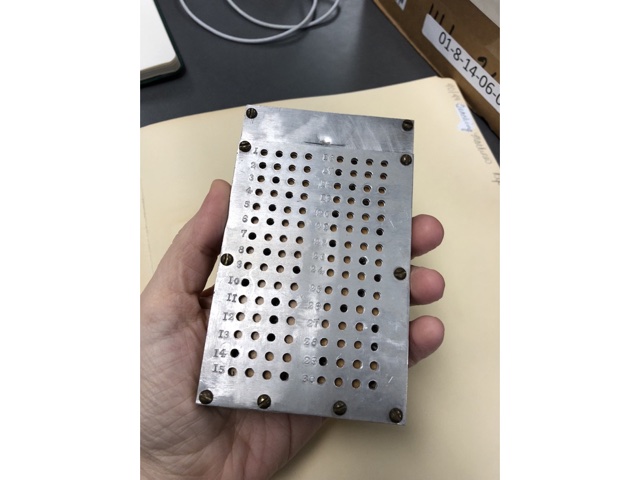

Pressey’s machine administered a multiple-choice test: “What does perjury mean?” read one question. “(1) Lying (2) Swearing (3) Slander (4) Gossip.” The test was fed into the machine on a sheet of paper just as one would load a piece of paper into a typewriter. The test-taker had four keys with which to respond, and after selecting her answer, the machine would advance automatically to the next question, calculating the number of correct responses along the way. Alternately, a lever in the back could change its operation slightly, and the machine would not move on to the next question until the test-taker got it right, tabulating the number of tries on each question. Pressey’s prototype also included an optional feature in which the teaching machine would dispense a candy when the student got the question right.

The “Automatic Teacher” wasn’t Pressey’s first commercial endeavor. In 1922 he and his wife published Introduction to the Use of Standard Tests, a “practical” and “non-technical” guide meant “as an introductory handbook in the use of tests” aimed to meet the needs of “the busy teacher, principal or superintendent.” By the mid–1920s, the two had over a dozen different proprietary standardized tests on the market, selling a couple of hundred thousand copies a year, along with some two million test blanks.

But convincing a publishing house to print your standardized tests or textbook is a different thing altogether than convincing a factory to build your teaching machine.

Pressey wrote letter after letter after letter to potential manufacturers – typewriter manufacturers, adding machine manufacturers, coin-operated machine makers, makers of scientific equipment, explaining to them this new apparatus he’d built that he believed would automate teaching and testing, invoking the coming “industrial revolution” in education. He didn’t really flash his own academic credentials – unlike today’s ed-tech entrepreneurs he never once mentioned that he’d gone to Harvard. He didn’t talk too much about the commercial successes he and his wife had already had selling standardized tests to schools. He really rested his pitch to potential investors and business partners on this growing faith in American politics and American culture that education could and should be “scientized” – and psychologists were just the men to do it.

Pressey was rejected again and again and again and again.

In 1929, after three years of inquiries and rejections, Pressey finally found a company that seemed willing to manufacture his machine, the M. W. Welch Manufacturing Company, based out of Chicago, Illinois. The company had a thriving business selling furniture and laboratory supplies to schools, so it had a solid base of education customers and a good reputation.

Pressey insisted that it would be incredibly simple and cheap to build his machine. “You can just stamp out the parts,” he insisted in some of his letters. But producing even the simplest machines requires a rather elaborate process. Before you can manufacture it, you have to manufacture the tooling required for production. You have to design and manufacture the molds, that is, before you can manufacture what’s built from them. And Pressey could not stop tweaking the design. He wrote frequent and lengthy letters to Welch Manufacturing – sometimes several a week – peppering them with suggestions. “Please focus on the marketing,” the company would plead – although not in so many words. Pressey insisted that if the machines worked flawlessly, they’d sell themselves.

The machines did not work flawlessly. Welch needed to sell 250 in order to break even. They sold 127. Of course, the Great Depression didn’t help. Arguments for labor-saving devices – and that was really the crux of Pressey’s reasoning – didn’t go over well when so many people, including teachers, were out-of-work. The machines cost $15 each – more than what was spent per pupil on education at the time. (Roughly $275 in today’s dollars – so, the price of a Chromebook, I guess, but to be clear that’s now about 2% of what we spend, on average, per pupil in K–12 education in the US.)

It’s too easy, I think, to look at Pressey’s technologies and only see these as a way to speed up the grading of multiple choice assessments – only as a matter of instructional or administrative efficiency, that is. Automation as standardization – that’s the version or the implications of automation, I think, we think we know.

But automation, Pressey believed, was essential for individualizing education. In many ways, it’s an argument that should be very familiar to us today: teaching machines allow students to move at their own pace; they give students immediate feedback; they free up a teacher’s time “for her most important work,” as Pressey put it, “for developing in her pupils’ fine enthusiasms, clear thinking, and high ideals.” Pressey imagined his machine to be a technology of individualization, one that he and others since have insisted was necessitated by the practices and systems of standardization in schools, by the practices and systems of mass education itself.

This is why it’s so significant that early teaching machines were developed by psychologists and justified by psychology – very much a science of the twentieth century. After all, psychology – as a practice, as a system – helped to define and theorize our conceptualization of individual, “the self.” Self-management. Self-reflection. Self-help. Self-control.

Individualization through teaching machines is therefore a therapeutic and an ideological intervention, one that’s supposed to act as a salve in a system of mass education. And this has been the project of education technology ever since.

But Pressey’s first teaching machine didn’t sell, and publicly admitted defeat in 1932. “The writer is regretfully dropping further work on these problems,” he wrote in a School and Society journal article on teaching machines. “But he hopes that enough has been done to stimulate other workers.”

And the work continued.

Indeed, Pressey himself continued to invent other technologies (and promote other technologies) he believed would “personalize” or in his words “individualize” education. (His later research interest included something he called “adjunct auto-instruction” – self-instruction, that is, facilitated by a technology, again so that students could move at their own pace.)

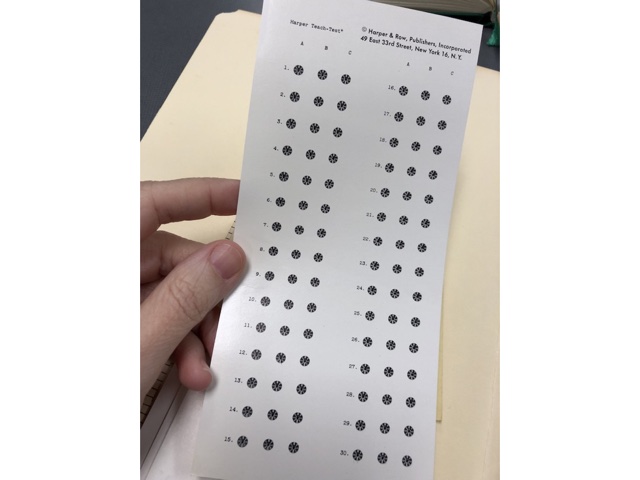

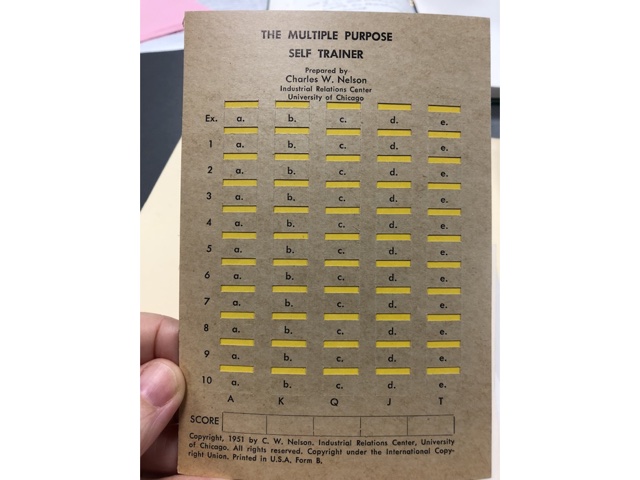

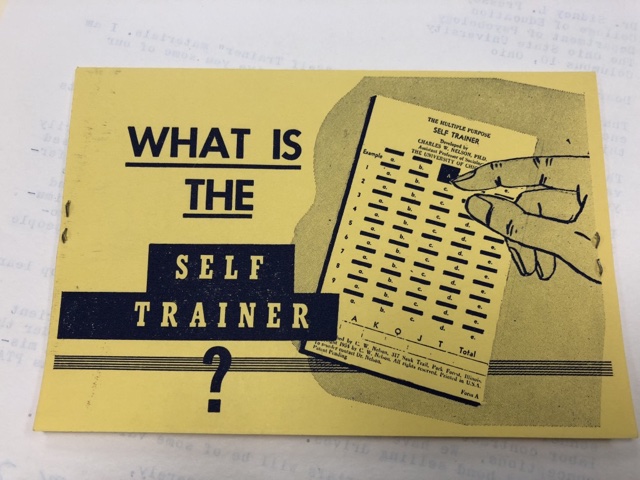

Let me show you some of these (but apologies for the not-so-great photos):

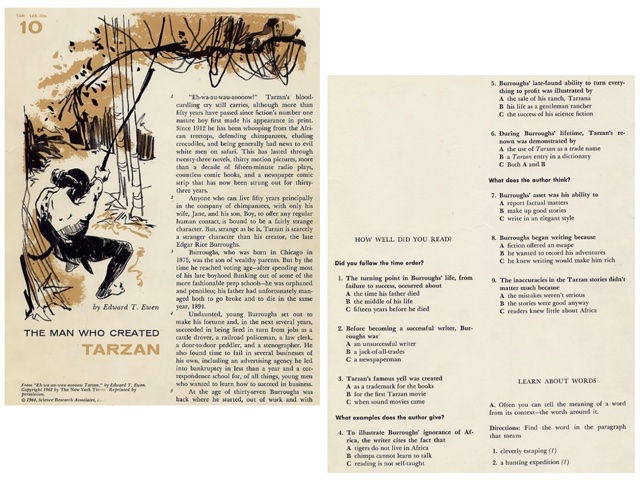

One of Pressey’s students first came up with the “chemo card,” a multiple choice test sheet that would immediately reveal if the student got the answer right or wrong. The student would use water in lieu of ink – a bit like those children’s water-activated coloring books.

A multiple choice test sheet in which the student erased the answer they thought correct, revealing a T if the answer was correct.

There was a “pluck card” in which a student would scratch off an answer, and again see right away if the answer was right or wrong.

There was a punchboard that would slide underneath the test sheet and if the student had the answer correct, the pen would go all the way through the paper to puncture a hole.

Lest you think “machines” weren’t involved, there was an electronic version of this in which a board would light up to indicate a right or wrong answer. The Navy worked with Pressey on a number of teaching machines in the 1960s, including a key pad installed into classroom chairs so that students could respond to quizzes and the instructor could see the results. (I love it that a certain Harvard professor thinks he invented “classroom response technologies” and practices in the 1990s.)

The US military is an important node in ed-tech’s historical network. So is another company, IBM, which despite Pressey’s failure to commercialize his teaching machine in the 1930s first brought its automatic test scoring machine on the market in 1937.

Here’s another interesting node: Science Research Associates, which manufactured a punchboard like Pressey’s. Perhaps you’re familiar with this company, better known as SRA. Here is the piece of personalized learning tech I used as a kid, the SRA Reading Cards. Does anyone know who founded Science Research Associates? Lyle Spencer. (Who also founded the Spencer Foundation, that’s paying for my fellowship at Columbia. Small world.)

I want to end here with a couple more thoughts on “personalization” and education technology. If we recognize that “technology” is much more than computers, much more than machines – that technology involves practices and systems and language and beliefs – then we can see that there is a long history of “individualization,” particularly as it’s been intertwined with psychology, particularly as it’s been intertwined with intelligence and aptitude testing.

There’s also been a privileging of self-instruction, particularly as these individualizing technologies were implemented to train men – and again, this is mostly a story about men – in science and technology in a post-Sputnik world. Tressie McMillan Cottom has spoken of the “roaming autodidact” as the imagined ideal student – imagined and idealized, that is, by the ed-tech industry, by the promoters of MOOCs and the like. It’s a student unconstrained by materiality, by the body, by place – by race, gender, geography. But I think this autodidact has been the imagined ideal for a long time. The atomized individual moving through atomized content modules filling out little circles and pressing little buttons.