This is the transcript of the talk I gave this afternoon at a CUNY event on "The Labor of Open"

Thank you very much for inviting me here to speak to you. I’m quite honored to get to kick off your event here, and I hope I can say some things that will be provocative and maybe generative for the kinds of discussions you’re having today.

As I’ve thought about what I might say, I will admit, I had to do a lot of reflection about what my relationship is to “open.” Because it’s changed a lot in the last few years.

I don’t want to make this talk about me. That would be profoundly unhelpful and presumptuous. But I also don’t want to make that word “open” do work politically (or professionally) that it hasn’t done for me personally (politically and professionally). And while I understand that for many people “open” is a key piece of an imagined digital utopia, it hasn’t been always so sunny for me.

At the beginning of the year, I made a bunch of changes to my websites – that is, my personal website and Hack Education, the publication I created almost a decade ago. I changed the logo. I updated my author photo. And I got rid of the Creative Commons licensing at the footer of each article.

My websites have always been CC-licensed – although admittedly, I’ve used different versions over the years, mostly going back and forth with whether or not I want that non-commercial feature. I guess, in some people’s eyes, that means my work was never really, truly “open.”

I thought a lot about this change, about ditching the CC licensing – this is my work, after all, and as such, it’s deeply intertwined with my identity. It’s also my experience – my lived experience – as a woman who writes online about technology.

Five years ago, I removed comments from my website. Lots of folks were not pleased. But dealing with comments was a kind of labor that I was no longer willing to do.

I’d written a couple of articles that had ended up on the front page of Reddit and Hacker News – articles critical of Codecademy and Khan Academy, in particular – and my website was flooded with comments signed by Jack the Ripper and the like, chastising me, threatening me. “Just delete those comments,” some people told me. “Flag them as spam.” But see, that’s still work. Not very rewarding work. Emotionally exhausting work. Seeing an email appear in my inbox notifying me that I had a new comment on my site made me feel sick. So I removed comments altogether – that’s the beauty of running your own website. I felt then and I feel now that I have no obligation to host others’ ideas there, particularly when they’re hateful and violent, but even if they’re purportedly helpful – “there’s a comma splice in your last sentence.” Or “It’s a little off topic but anyone looking for a job should check out this website that is currently hiring people to work at home for $83 an hour.” You know. Helpful comments.

Since then, annotation tools like Hypothes.is and Genius have become popular. And even though I didn’t want comments on my website, these companies have built tools so that people could mark up my writing on my websites nonetheless. The comments weren’t literally on my website; they’re an additional layer, if you will, on top of my writing – hosted elsewhere, outside my control (and, I suppose, outside my responsibility, my “work”). So I added a script to my site that made it impossible for these tools to function on Hack Education and on my personal blog. As I wrote then to explain my decision,

This isn’t simply about trolls and bigots threatening me (although yes, that is a huge part of it); it’s also about extracting value from my work and shifting it to another company which then gets to control (and even monetize) the conversation.

(The response from the head of Hypothes.is was “but we’re a non-profit.”)

I also wrote on my site,

Blocking annotation tools does not stop you from annotating my work. I’m a fan of marginalia; I am. I write all over the books I’ve bought, for example. Blocking annotations in this case merely stops you from writing in the margins here on this website.

When I wrote this, my work was still CC-licensed, so as long as folks followed that – redistributing it with attribution for non-commercial purposes – they could post an article from Hack Education elsewhere and mark it up to their hearts’ content there. But as people responded with outrage at my decision to control what happened on my website, in my personal digital space, I confess: I became increasingly irritated. I was told that because I’d published something online, anyone could do what they wanted with my work. I was told that I was silencing dissent. I was told I was being irrational, controlling – “authoritarian” someone called me. All because I’d disabled some JavaScript on my website.

Now, nothing can stop you from writing in the margins of my work. I can’t stop you. I have never tried to stop you. I’ve never hired lawyers to stop you. You can print it my essays and scribble all over them. You can buy a copy of my books – in digital or in print – and you can mark those up too. You can take an excerpt and add your own commentary. You can highlight the comma splices and point out the typos. You can call me names and tell me to get back in the kitchen.

But because I’ve removed the Creative Commons licensing, you now do have to do one thing before you take an essay of mine and post it elsewhere: you have to ask my permission.

As a woman who writes online about technology, I have grown far too tired of “permission-less-ness.” Because “open” doesn’t just mean using my work for free without asking. It actually often means demanding I do more work – justify my decisions, respond to accusations, and constantly rethink how and where I want to be and am able to be and work on the Internet.

So I’ve been thinking a lot, as I said, about “permissions” and “openness.” I have increasingly come to wonder if “permission-less-ness” as many in “open” movements have theorized this, is built on some unexamined exploitation and extraction of labor – on invisible work, on unvalued work. Whose digital utopia does “openness” represent?

Perhaps it’s worth looking at history of the idea that the Internet is utopian in its founding or in its intent – at “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” for example, at its claim that “Cyberspace consists of transactions, relationships, and thought itself, arrayed like a standing wave in the web of our communications.” Transactions and relationships, the declaration notes, but it makes no mention of work or pay or labor or costs. “Ours is a world that is both everywhere and nowhere,” the declaration proclaims – the “no place” of utopia, no doubt, “but it is not where bodies live.” You know, I felt every one of those death and rape threats in my body. I have had to fear for my body when I’ve shown up some places, in person, to speak.

I like to remind people that with all this sweeping rhetoric about revolution and transformation, that John Perry Barlow wrote “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” in 1996 in Davos, Switzerland, at the World Economic Forum. I don’t know about you, but that’s neither a site nor an institution I’ve never really associated with utopia. Indeed, perhaps much of this new technology was never meant to be a utopia for all of us after all.

“On behalf of the future,” Barlow wrote, “I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.”

Who does have sovereignty in this vision of the future? Who labors, who manages? Who is welcome? And if there are those who are unwelcome – and clearly there are – what does that mean when something like “open” gets invoked to talk about this digital space? What does it mean that some of the people and places and documents and diatribes that those in digital technology’s “open” movements point to as their inspiration, as their origin stories, as the past and the future of “cyberspace,” are deeply committed to misogyny, to racism. (It’s 2018, by the way, and if your slide-deck on “open” still contains pictures of Eric S. Raymond or Linus Torvalds then I’m just going to assume your idea of “open” has not thought about power relations at all. Your message, to echo Barlow, “you are not welcome among us.”)

And I don’t mean here, how do we trace history through a different set of voices? I mean, how might “open” and “digital” be built on precisely these beliefs – on exploitation and exclusion and violence?

When we think about “open” and labor, who do we imagine doing the work? What is the work we imagine being done? Who pays? Who benefits? (And how?)

I talk a lot in my writing about “the history of the future” – that is, the ways in which we have, historically, imagined the future, the stories we have told about the future, and perhaps even the ways in which those narratives shape the direction the present and the future take.

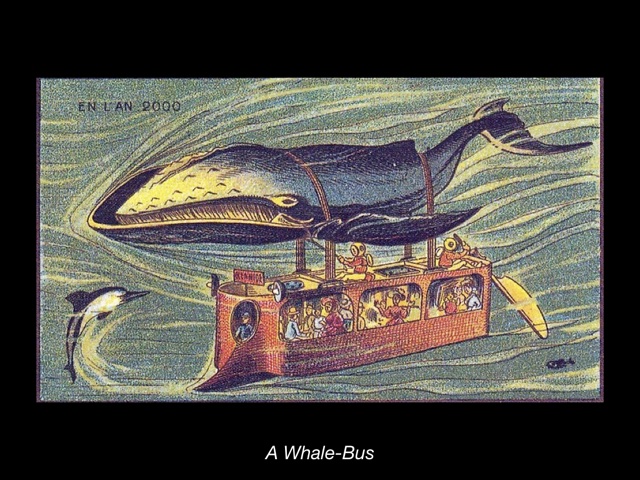

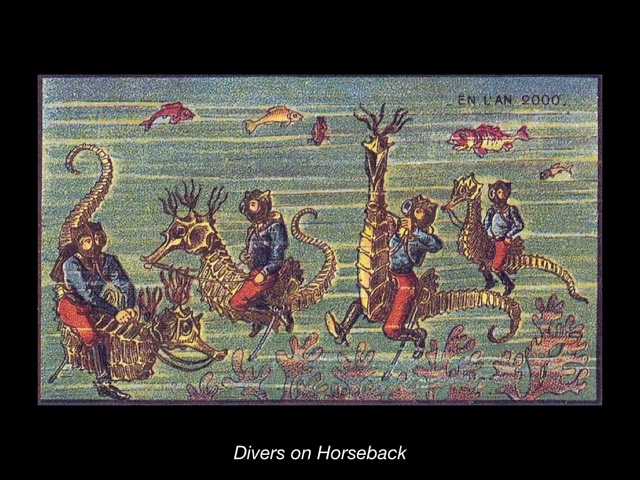

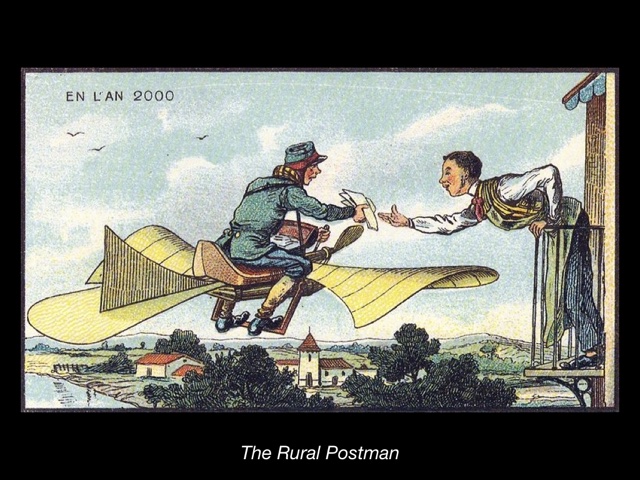

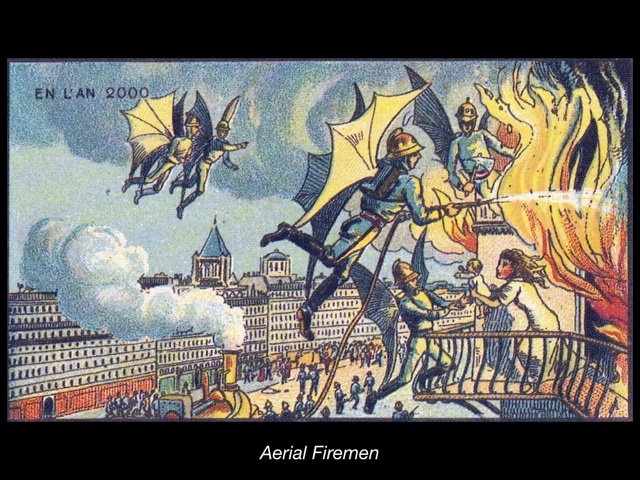

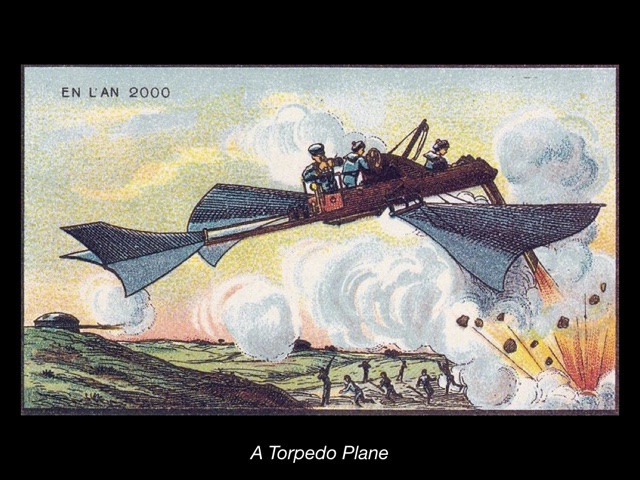

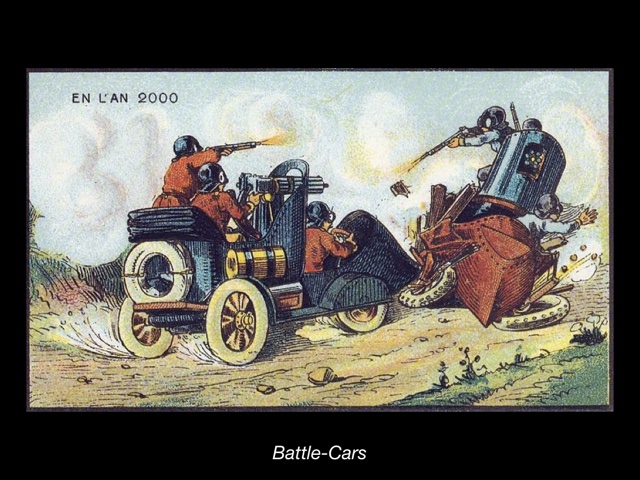

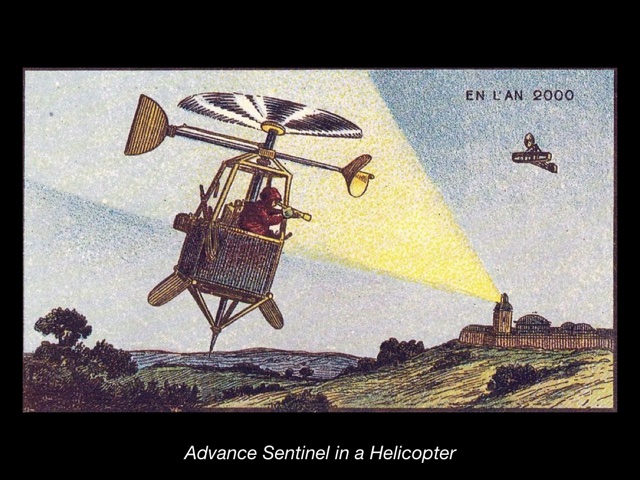

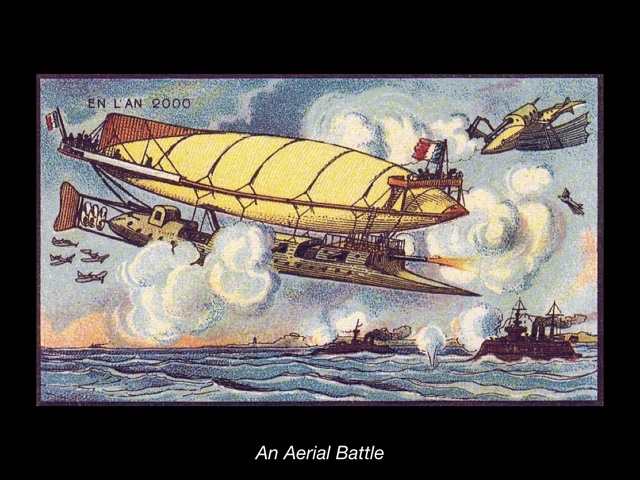

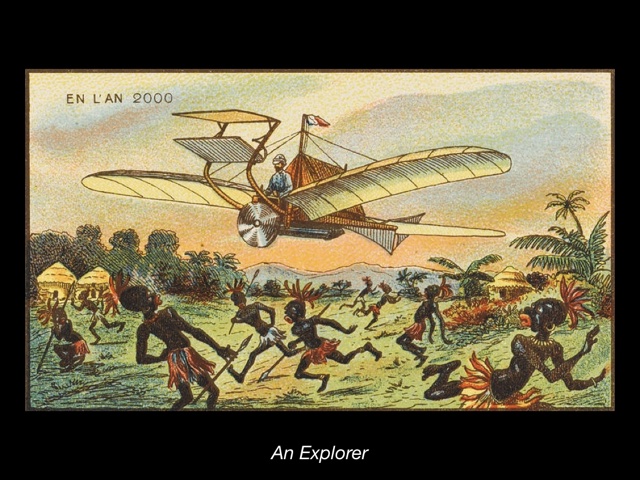

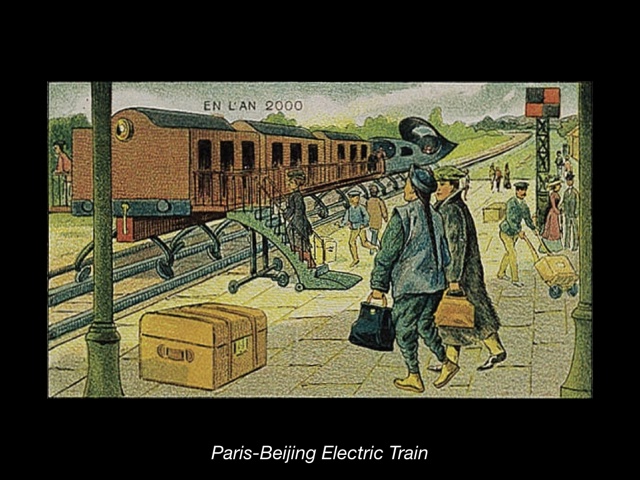

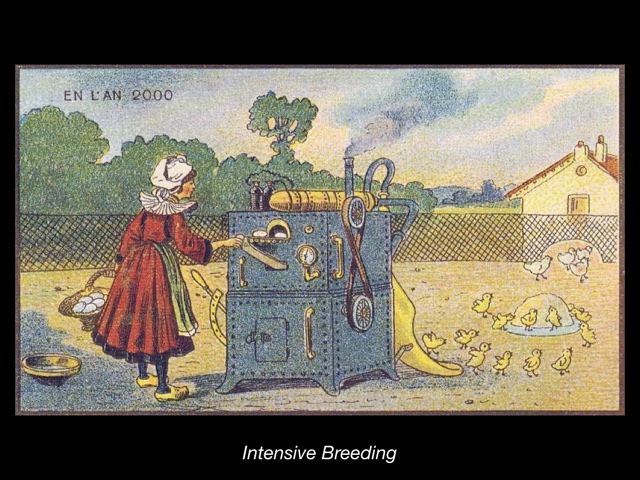

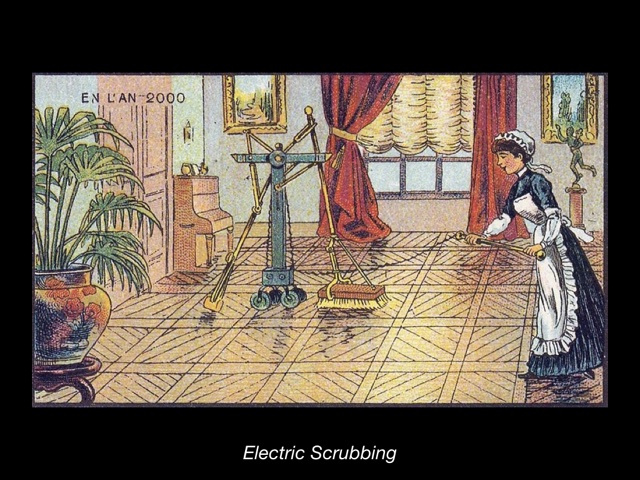

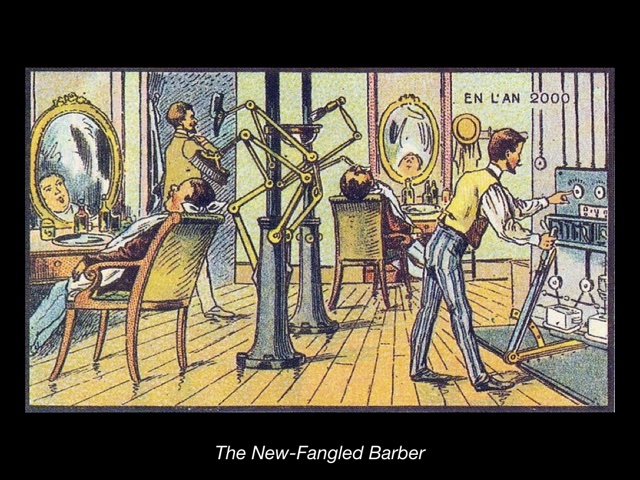

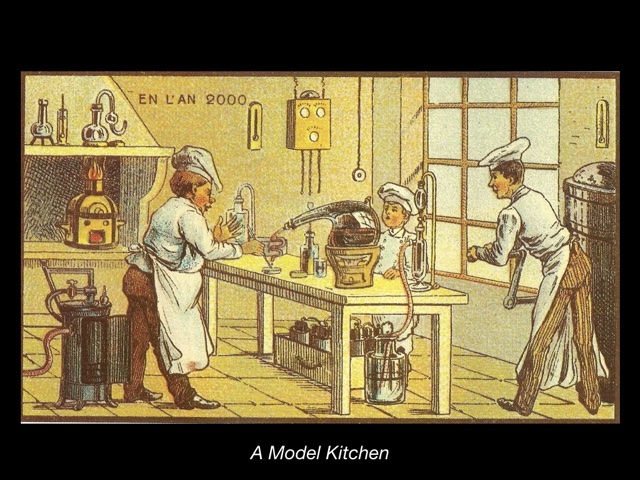

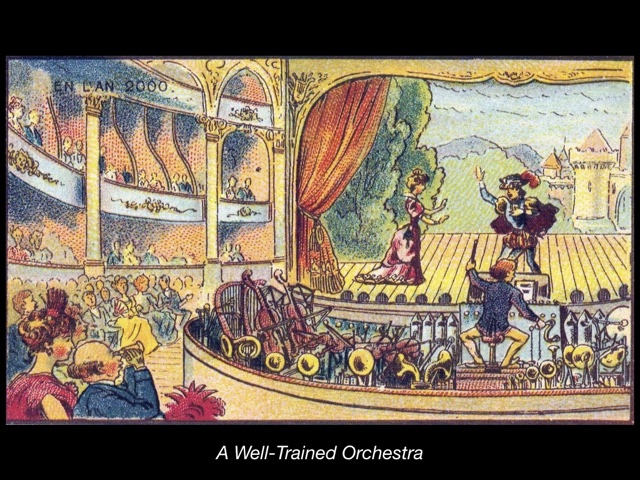

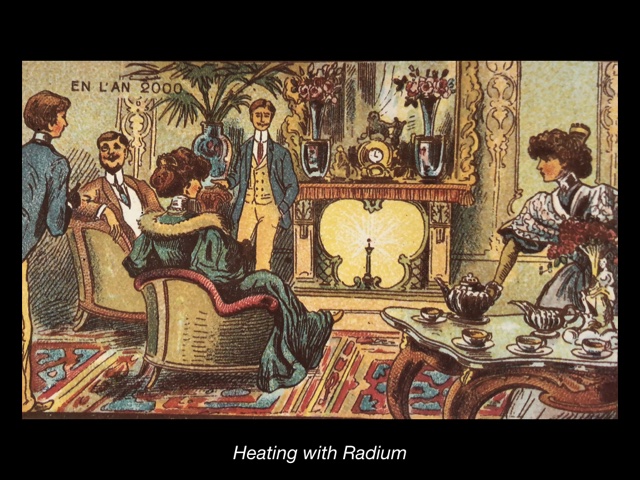

I’d like to turn to some of of these depictions of the future, a series of postcards that were created in 1899 in France to celebrate the turn of the century and to imagine what the world might be like in the year 2000.

I’ve used one of these images many times in talks – it’s so perfect. It reveals so much about how we imagine (how we have long imagined) the future of education. This illustration depicts a classroom in which the schoolmaster stuffs textbooks, including L’Histoire de France, into a machine. A student turns the hand-crank, and the machine grinds the books into information, delivering it via electrical wire to the helmets – and we can assume into the minds – of the schoolboys, all sitting pensively with their hands crossed on their desks.

(This is an illustration of school. This is an illustration of knowledge. This is an illustration of imperialism. This is an illustration of whiteness and maleness. This is an illustration of work.)

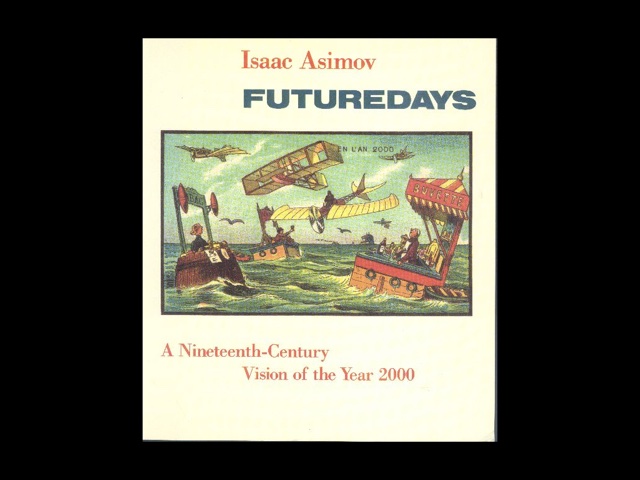

Isaac Asimov published a book collecting and commenting on these illustrations in 1986 – so still over a decade before the year 2000 – and this is how he described this particular image:

Presumably, the students hear the information in the books as it is automatically converted into sound, which, one gathers, impresses itself on the young minds more efficiently than would be the case if the teacher read the books aloud or if the students read to themselves. While this is not likely to happen, either now or in the future, we are indeed likely to have an education revolution by 2000 but it will, of course, involve the increasing use of computers as storehouses and deliverers of information."

Computers, not books. Computers, not electrical wires and helmets.

As Asimov’s interpretation should remind us, throughout the twentieth century (and on into the twenty-first), the future of education (and more broadly for your purposes as librarians, the future of scholarship, knowledge-building, and knowledge-sharing) has been imagined again and again as a highly technological endeavor where machines streamline the efficiency of teaching and learning.

The efficiency of teaching and learning – that means we need to talk about labor, in this illustration, in our imagined futures, in our stories. Because it’s not just the machine (or it’s not the machine alone) – in this depiction or in our practices – that is doing “the work.” There is invisible labor here. Not depicted. Not imagined. Not theorized or commented upon by Asimov.

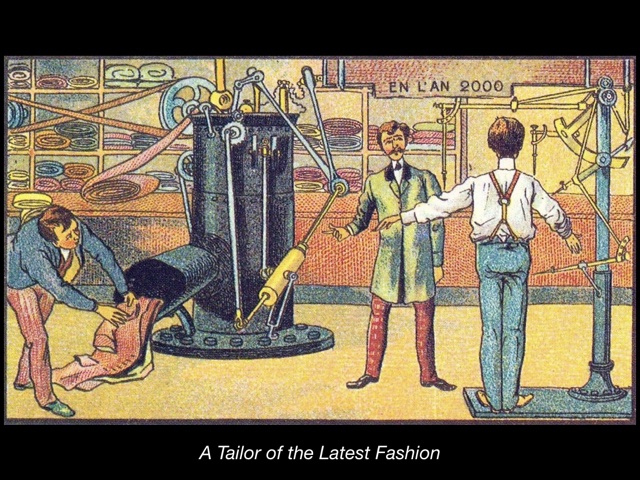

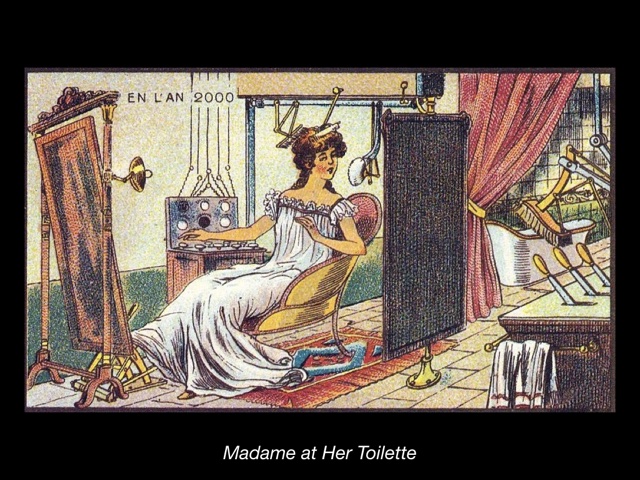

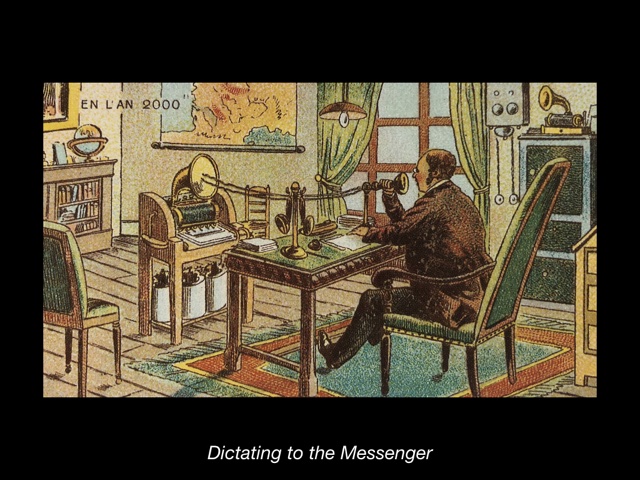

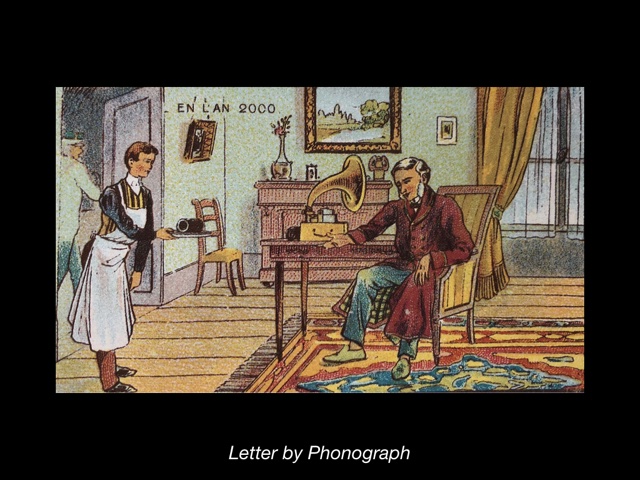

Indeed, almost all the illustrations in this series – and there are 50 of these in all – involve “work” (or the outsourcing and obscuring of work). Let’s look at a few of these (and as we do so, think about how work is depicted – whose labor is valued, whose labor is mechanized, who works for whom, and so on. And if you’re familiar with these illustrations, think about those that are regularly used in talks like this and those that have you never seen before – why):

(A sidenote: I included this illustration because I think it is a mistake to ignore the imperialism in this vision of the future. Ignoring racism in the technological imagination does not make it go away.)

What do machines free us from? Not drudgery – not everyone’s drudgery, at least. Not war. Not imperialism. Not gendered expectations of beauty. Not gendered expectations of heroism. Not gendered divisions of labor. Not class-based expectations of servitude. Not class-based expectations of leisure.

And so similarly, what is the digital supposed to liberate us from? What is rendered (further) invisible when we move from the mechanical to the digital, when we cannot see the levers and the wires and the pulleys.

One note here about these illustrations – because I want to make it clear that the problems we face with digital labor and digital utopias are not necessarily simply about the digital but rather about systems and structures that have long been in place: These cards were commissioned by a novelty toy maker in Lyon, France called Armand Gervais. A freelance artist named Jean Marc Côté was hired to draw them. According to the Canadian science fiction writer Christopher Hyde, Côté finished the drawings in the summer of 1899, and then he “sank into obscurity.”

Obscurity – there’s that process of erasure once again. Invisible labor. Labor obscured.

Nothing else is known about Côté, says Hyde. In late 1899, the founder of Armand Gervais died, and the company went out of business. The cards were never distributed. Hyde bought the cards – this set of 50 – from an antiques dealer who, in the late 1920s, had sought to purchase the abandoned Armand Gervais factory. While touring it, that man had discovered a trap door – or so the story goes – that revealed a store room where all the items that had been manufactured for sale were placed when the factory closed its doors. Found among them was this one set – one complete and undamaged set – of illustrations. The antique dealer sold them to Hyde who showed them to Isaac Asimov who reprinted them in his book Futuredays. The illustrations were in the public domain – “open” and outside of copyright protection, that is. But we can see in the production of this book that there are layers of labor that are lost and obscured when Isaac Asimov’s name is listed as author. (Côté’s name does not appear on the cover.)

And to be clear too, in his commentary that accompanies the illustrations, Asimov is no better at predicting the future – the shape of the year 2000 – than Jean Marc Côté was in the images he’d drawn one hundred years prior. Both are caught up in the same sort of imperialist and technological imaginations of manhood and “man’s work” and machine that Jules Verne, inspiration for the genre of science fiction and for these very illustrations, was more than a century ago.

Chronicling the technological advances of the twentieth century – since Côté drew his illustrations – Asimov writes in the book’s introduction, “all these things mean change, change, change – one way change, progressive change.” “In fact, it is possible to argue,” he adds, “that not only is technological change progressive, but that any change that is progressive involves technology even when it doesn’t seem to.”

I’ve got some significant quibbles with this. It does make for a nice story about human history – I think there’s a Harvard professor making the rounds peddling a new book that makes a similar sort of claim: we are becoming less violent and more altruistic. Things get better. Asimov’s statement makes for a powerful story about technology too: that technologies, not people, have historical agency; that new technologies are inevitable, necessary, and above all, good; that these advances are intertwined with Enlightenment ideals of reason and liberalism and science. That the machine is, as such, liberatory. That the machine is utopian even – or at the very least, that it pushes us in that direction.

My theory for social change does not posit that technology is the (or even an) actor. That is, I do not believe, to borrow from the title of one of Kevin Kelly’s books, that social change (progressive or otherwise) is “what technology wants.” My theory for social change rests on the political struggle of people, on collective social action.

And that’s work.

And it’s work not often imagined in digital utopias. (Collective action hardly makes an appearance in Jean Marc Côté’s illustrations, with the exception of fire-fighting and war and wealthy people sitting around a radium “fire.”) We can speculate on why this might be. Perhaps it’s because machines are supposed to enhance productivity. Perhaps because we’re more eager to talk about people as consumers than as workers. Perhaps it’s the emphasis on leisure rather than labor. Perhaps it’s that today’s “platform capitalism,” as Nick Srnicek argues, extracts our data not just our labor. Perhaps because futurists rarely talk about reproductive or affective labor. Perhaps because we’re “knowledge workers” now and as John Perry Barlow argued in his “declaration of independence” that is “not where bodies live” – knowledge work is pure thought, pure mind, pure intellect.

If digital utopia doesn’t see our bodies, it makes sense it cannot see our work. If digital utopia cannot imagine our existence, it makes sense it will not value our presence (or notice our absence).

Of course, that also might mean it won’t expect our resistance. (Even if our resistance is as small as blocking some JavaScript on our personal websites… but I’m guessing this group will think and act bigger.)