Arguably one of the most controversial pieces of education technology to enter the classroom has been the calculator.

Certainly some classrooms long ago sanctioned the use of a different sort of calculating instrument, the slide rule. But the calculator seems to evoke all sorts of fears that students’ computational abilities would be ruined, that students would become too reliant upon machines, that they wouldn’t learn how to estimate, that they wouldn’t learn from their errors.

Some of the arguments from proponents of calculators sound much like the arguments for ed-tech today: students must learn how to use these modern devices in order to find their way (a job) in the Information Age.

Calculators, particularly once sanctioned usage for use in standardized testing, also raised questions about ed-tech and equity: does an expensive scientific or graphing calculator – one that offers more than the four basic arithmetic functions – give affluent students a bigger advantage in these exams? (The cost of a graphing calculator today: anywhere from $50 to $175.)

Building Calculating Machines

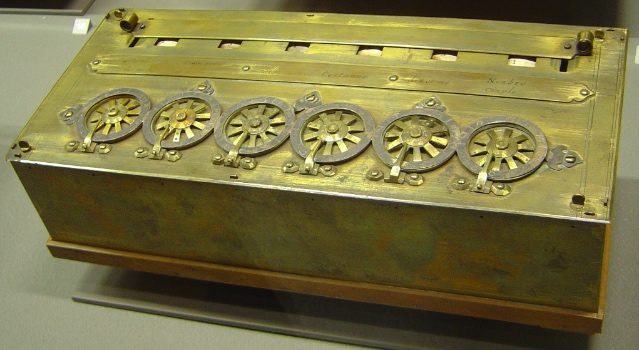

Calculating machines such as the abacus have existed for thousands of years, largely unimproved upon until the 17th century when mechanical devices were built that could add, subtract, multiply, and divide. Although several people offered different designs, Blaise Pascal is the one often credited as inventing the calculating machine. (He was, at least, the first to receive a patent – the Royal Privilege – in 1649, which granted him exclusive rights to make and sell calculating machines in France.)

Almost two hundred years later, the Arithmometer became one of the first commercially successful calculating machines. Patented in 1820 by Thomas de Colmar, industrial production of the machine began in 1851. The machine was not only reliable but durable and was adopted for use in banks and offices.

Early electronic calculators were, like their computer cousins, rather large – desk-size not even desktop, built with vacuum tubes and later transistors. The Casio Computer Company’s Model 14-A, released in 1957:

In 1958, Texas Instruments engineer Jack Kilby demonstrated the first working integrated circuit, which has since enabled cheaper, smaller, and better performing computing devises. Almost a decade later, in 1967, TI engineers developed the first handheld electronic calculator.

Thanks to a number of technical developments (the integrated circuit, for starters, along with LED and LCD), these portable computing devices quickly got better and cheaper. In the early 1970s, calculators could cost several hundred dollars, but by the end of the decade, the price had come down to make them much more affordable and much more commonplace.

Calculators (Not) Allowed

Calculators had already become important business tools, well before the handheld calculator. And in the 1970s, with a fair amount of debate about their effect on learning, calculators slowly began to enter the classroom.

Calculators had already become important business tools, well before the handheld calculator. And in the 1970s, with a fair amount of debate about their effect on learning, calculators slowly began to enter the classroom.

Indeed, once students had access to calculators at home, it was pretty clear that they would be used for homework no matter what policies schools had in place for classroom usage. (A 1975 Science News article, “Calculators in the Classroom,” claimed that there was already one calculator for every 9 Americans.) While the general public debated whether or not calculators should be allowed at school, educators were forced to grapple with how the devises would change math instruction.

In 1975, the National Advisory Committee on Mathematical Education (NACOME) issued a report on calculators, suggesting that those in eighth grade and above should have access to them for all class work and exams. Five years later, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) recommended that “mathematics programs [should] take full advantage of calculators … at all grade levels.”

In 1986, Connecticut became the first state to require the calculator on a state-mandated test, as the Connecticut School Board argued that calculators would allow students to solve more complex problems. Other states followed, some ponying up to pay for students’ calculators. New York, for example, allowed calculators in its Regents exam in 1991, mandating their use a year later. In California, however, the Board of Education prohibited calculators on its statewide assessments in 1997.

The College Board allowed students to use calculators on the Advanced Placement Calculus Exam beginning in 1983, but a year later reversed its policy, banning the devices claiming that it wasn’t fair for students who didn’t have a calculator. A decade later, the College Board mandated calculators’ use on the test.

In 1994, as part of larger revisions to the exam, the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) also allowed calculators. This is often positioned as the tipping point for calculators being “okay.” That year, 87% of students brought a calculator to the test; by 1997, 95% of students did so.

Which Calculators for Which Students?

According to research published in 2002 by Janice Scheuneman and Wayne Camara (PDF), girls used calculators on the SAT exam much more often than boys. White students used them more often than other racial/ethnic groups. Those who used calculators performed better on the SAT than those who didn’t – but the type of calculator mattered significantly: students who used graphing calculators outperformed those with scientific calculators, and those who had only a four-function calculator performed only slightly better (~20 points) than those who didn’t use a calculator at all.

“Every question in the mathematics portion of the SAT can be solved without a calculator,” the College Board insists. Today it allows battery-operated, handheld calculators – all scientific calculators and all four-function ones (although it doesn’t recommend the latter). It also allows the following graphing calculators:

Cell phones, smartphones, laptops, and tablets are not allowed, despite calculator functionality. Graphing calculator apps like Desmos, despite in Desmos' case being free and awesome, are also not allowed.

Various other standardized tests and professional exams allow different models of calculators. Almost always on the list of approved devices: Texas Instruments calculators. (TI’s lobbying expenses haven’t changed much in the last decade; its name and brand, perhaps already synonymous with school-approved calculators.)

What Do Calculators Do (To Math Class)?

In some ways, it’s difficult to separate debates about the usage of calculators in the classroom from debates about math education writ large. Much of the “Math Wars” of the late 1980s (and onward… still) involved how much technology was appropriate, what technology would mean for the acquisition of basic math skills, and what - thanks to new technologies - math education should or could look like (what math curriculum should or could like at the K-12 level, as well as what it should or could like in college.)

As Sarah Banks notes in her study of the changing attitudes towards calculators,

The NCTM likened new mathematics classrooms with calculators and computer software to science classrooms or laboratories. Students should discover, make conjectures, and determine their correctness in mathematics curriculum as well. The organization also cites another advantage of increased calculator use will be improved student interest, stimulating classroom environments, and higher student self-concept.

Some forty years after the calculator first entered the classroom, these questions still have not been resolved. (See: Education Week‘s look at calculators and the Common Core assessments.) Some of the hope and some of the panic have shifted to other computing devices – cellphones for example; some of the panic has spread to these machines’ facilitation of cheating.

You can read the comments on almost any story today about math education and see these same, long-running debates: fears that students’ computational abilities will be ruined by calculators/computers/cellphones, that students will become too reliant upon machines, that they won’t be able to learn from their errors and teachers won’t be able to help them, that they won’t learn basic skills.

Ed-tech: plus ça change…